ruminating about the meaning of music with roméo poirier

Hailing from Strasbourg, Roméo Poirier had always been making music for as long as he can remember. He currently lives in Brussels, so we met up with him for a chat. We talked about his fascination for water, his love for languages, and his never-ending quest for music. Though much of the conversation was dominated by buzzing wasps, it didn’t stop Roméo from sharing what’s on his mind.

What brought you to Brussels?

Together with a group of friends, we decided to do a collective move to Brussels six years ago. When you live in the same place for a long time, you become entangled with memories. Strasbourg became too familiar of a place to me, and it’s liberating to do something fresh and free.

And do you feel at home here in Brussels?

There’s an appetite for experimentation here in Brussels and a lot of cool things are also happening here musically, so it’s a good place to be.

How did you get into music?

I started playing drums at 5 years old with my father. He was in a rock band in France which enjoyed quite some success in the 90s and early 2000s. It was called Kat Onoma. It’s not really well-known but I think they were a really good band. I was following them in the studio growing up.

I was also into pop music at some point in Strasbourg. Together with a girl named Sarah, we had a two-person band singing easy-going songs in English. Our band was called Roméo & Sarah.

Do you see pop music and your own music as two different worlds or rather a combination of a whole?

I like to have a foot in the world of pop music. Pop music is often very immediate and brings things back to the essentials very quickly. I like the efficiency of it.

Pop music is also music made to be popular, so it’s music designed to be listened to by a large amount of people. The purpose is good, because you want music to find the most resonance possible. You don’t want your music to be put in a tiny box.

Are there elements from pop music you bring to your own music?

Yeah sure. I don’t really play instruments in my own music anymore, but I do play the trumpets every now and then. To me, the trumpet symbolizes the voice. It can have the same presence and texture.

What is your relationship with music?

Before being born, hearing is the first sense you develop. You don’t hear a properly articulated language, but you hear sounds and prosody, which is the musicality of the language.

The quest for a musician could be the search for something you know already, even before you are born. What I am trying to do as a musician is to create an echo of this sensation of the prenatal prosody.

And in trying to create this echo, I’m learning to find my own way of amplifying my music. I have to define in what space I want the music to resonate. I really believe without amplification, music won’t really be music.

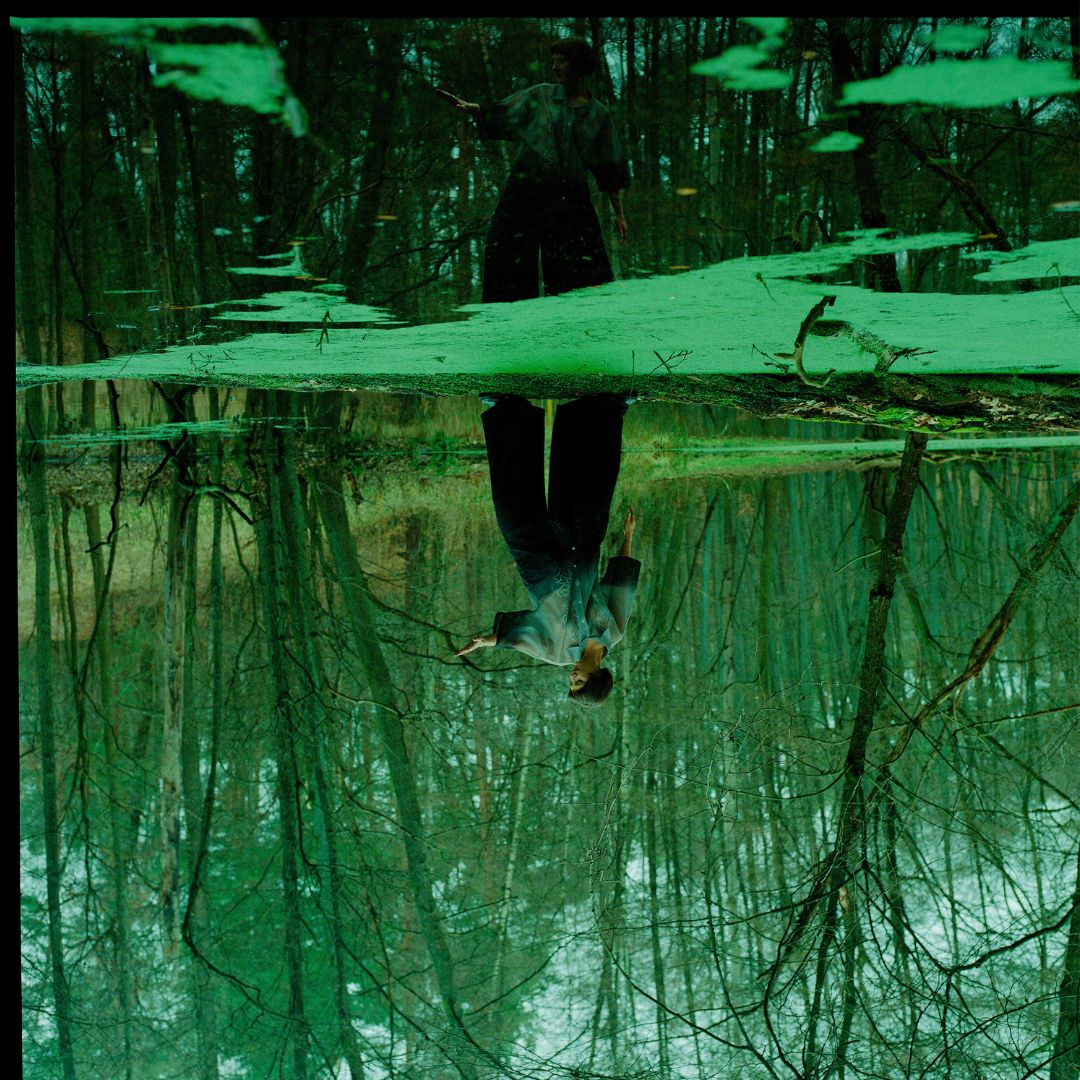

That’s a really profound way of describing your quest. What is your fascination with water, as a lot of your releases seem to share this theme?

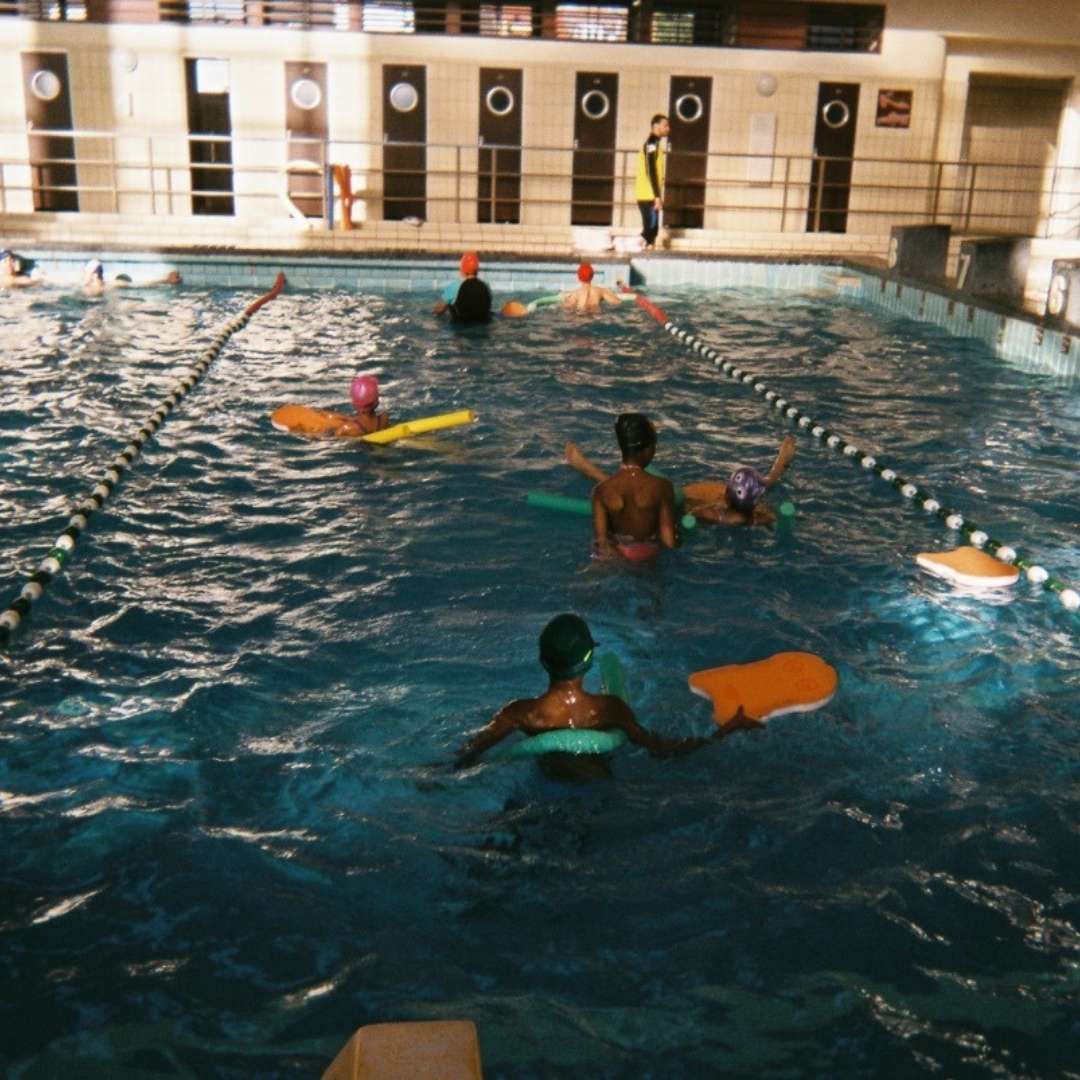

As a kid, I was really fascinated with the submarine gear and it was a big dream of mine to own a full diving suit. I started to develop this phantasm of all things submarine and apnea records from Jacques Mayol. After following this attraction with water, It got to a point where I just needed to get out of this phantasm. That’s when I decided to become a lifeguard here in Schaerbeek at the Neptunium pool.

It was interesting for me because I had to break away from contemplation and change my attitude to be ultra-attentive in order to fulfil my duties as a lifeguard. I feel like constantly being on the lookout forced me to actively engage with and apprehend the world in a different manner. This change of perspective has certainly brought me closer to people.

Now I stopped being a lifeguard, and I think I finally understood the starting point of my music. For a long time, I thought I was intrigued by deep water. Going through the motions of it for around two years, I realized deep water is actually quite boring and I’m rather more inspired by water interacting with things. I really like the dynamic of the shore, a place where you have the limit between the water and the earth. It’s a territory that is always moving and redefining itself in flux.

Do you ever incorporate the shore, or the environment in general in your music?

No, I don’t, although I like the idea of the environment enhancing the music listening experience. When you are listening to a record for example, it can be nice to listen to it in silence, but it can also be equally nice to enjoy it while some other elements from the outside are coming in. Like some birds in the background or people talking over it. It gives a fresh perspective to the music.

Does your environment influence your music making?

When I make music, I need to be in a really calm setting or a familiar place. That doesn’t mean I need to isolate myself completely, but I have to be able to choose what I want to let in from the outside.

I have a new friend. A bird on my rooftop that is singing like crazy. It’s amazing how many songs it can sing. When I make music, the bird is often there and I think we make quite a good duo together.

You’ve released on a number of labels. How do you decide which label to release on?

Kit Records was a random encounter. I was just arriving in Brussels about five years ago and through a friend from Strasbourg I met a Scottish artist named Object Agency, who’s now also signed on Kit.

Richard Greenan from Kit contacted him to do a mix series and he included a song of mine at some point. Richard liked the song and we met online. He asked me if I had any music to release. I released four digital tracks under the name Swim Platførm. Everything was done digitally and I only met Richard in real life about a year later in London. At first, we had some difficulties understanding each other. I really had to get used to his strong accent. But we got along and I released a few more things on his label, driven by his enthusiasm.

I also really enjoyed working with Will Boyd for my latest record, Hotel Nota, on the Manchester-based label sferic. He really has a clear idea of what he wants to release, and was pushing me in certain directions. At some point, I thought I was done and he just told me that we’re not there yet.

One of your releases on Kit Records features Norwegian poetry. How did that come about?

This was another very random encounter. I like it when I meet people that don’t speak the same language as I do.

I had a roommate in Strasbourg who comes from Norway and I went to visit him once. His friends were very welcoming and offered to tour me around. During the trip, I met these twins in Bergen. One of them was Lars who at that time was writing poetry about whales and the movement they do when they die down.

Apparently, when whales die down, it takes a few days and sometimes even weeks before they reach the bottom of the sea. They have this very slow movement of falling. This was the starting point of Lars’ poetic movement. That exchange between music and poetry was how Kystwerk happened.

I don’t understand Norwegian, but I liked his voice because it sounded very steady. In Norwegian you don’t hear the lyricism in poetry as much as in French or in Dutch or in English. The lyricism is somewhere else, perhaps in the repetition rather than in the tone. Interesting just to hear a language without being aware of what it means. It probably goes back to that prosody experience I talked about earlier.

To me, it’s really a fascinating idea how music is not language but without language there would be no music. It’s fascinating how all of us listen to music even if it’s not really something we understand.

Do you actively seek out this encounter of languages?

The more you learn languages, the richer your thoughts and imagination seem to be. The more you have different words to use, the more you can elaborate. I unfortunately don’t speak Dutch yet, but I really like the language.

It’s quite cool that you are exploring different collaborations.

Yeah, it’s not always so fun to do things on your own. Some things need to be done that way. Some others don’t. It’s a balance. The balance also needs to be unbalanced sometimes. Music is mostly about repetition and surprise, as well as the familiar and the unknown.

Has the way you make music evolved a lot over the years?

I get the impression that I can better visualize a form, an idea and then realize it. It is trying to look for a form of abstraction by extraction. I often initially take a piece to its extreme. With that, I then cut back on the frequencies and instrumental sounds to make for a more refined, minimal piece. It is a quest, an attempt to find something—a lost music, before words, and to echo it. For me, music does not create an escape, rather on the contrary. Through an experience of immobile intensity, music refers to the most vivid aspects of life.

Last question for now, what is your favorite sound in the world?

I like voices a lot. I also like random sounds such as fire cracking or a drop of water hitting the fire. I like textural sounds like the voice too. I don’t really like clean sounds. I like it when the frequency spectrum is really full. I like it also when the sound has some noise. To me, there is this idea that the sound is transporting something from the past, almost like a ghost traveling forward in time.