Blurring time with Dmytro Nikolaienko

As modern technology keeps a foot firmly planted on the pedal, Dmytro “Dima” Nikolaienko finds creative pleasure in reversing gears and charting a course back to a dust-covered, grainy, and hauntingly romantic world of analogue sounds. He works with minimal equipment and a no-laptop policy, harnessing an intricate puzzle of tape loops where electro-acoustic elements and field recordings are carefully pieced together.

Aside from making his own music, Dima is the founder of the label Muscut and its sub-label Shukai. A shared timelessness runs through both musical outlets, with Muscut focused on contemporary releases that sit comfortably next to archival works, and Shukai offering a glimpse into the lost tapes of Ukrainian culture from the 20th century.

Dima’s approach to meaningful creation taps into the power of possibility, while his efforts in bringing the past into the present are vital for preserving the deep wells of inspiration that run through history.

What inspires your choice of sounds and textures when you start a new piece or album?

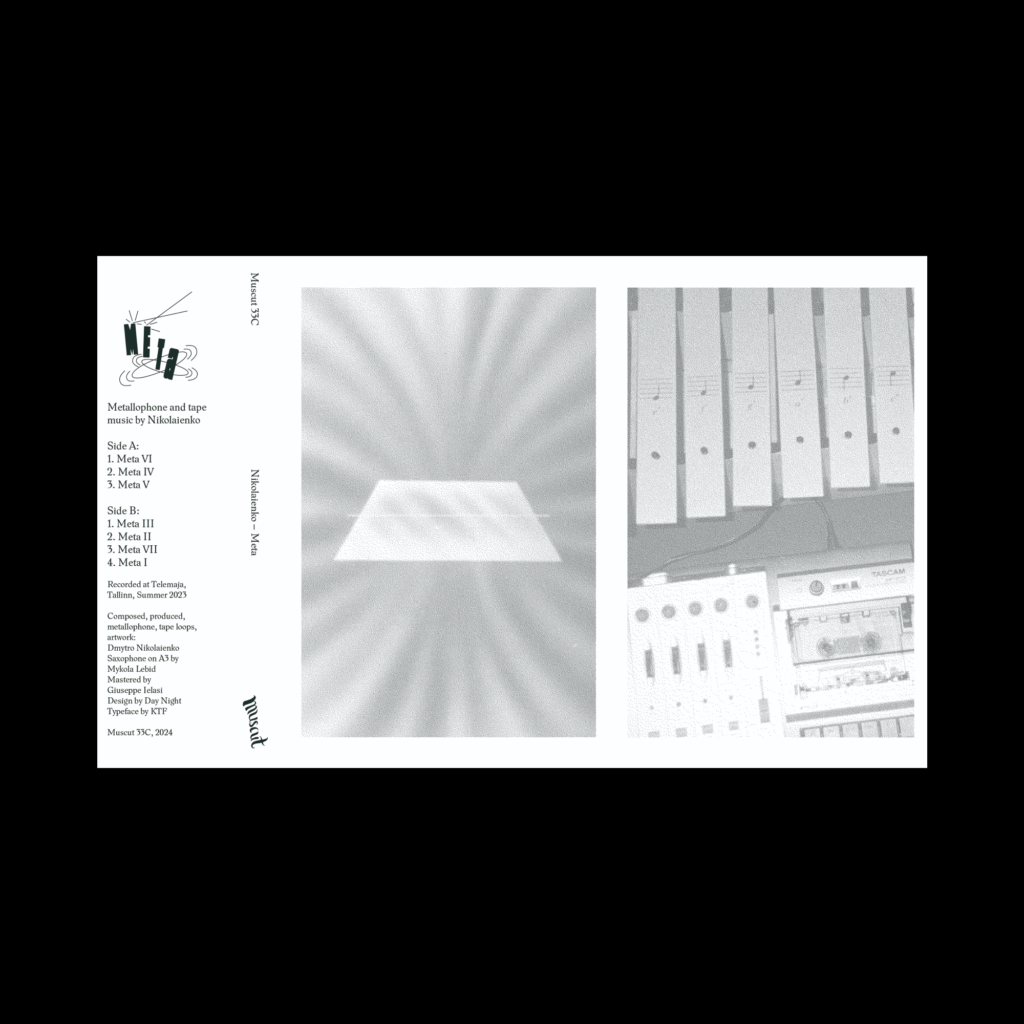

It usually stems from an idea for the album, which often leads to self-imposed limitations on the choice of instruments. In my previous albums, Rings and Nostalgia Por Mesozoica, I restricted myself to using only tape loops and a modular synth system as the primary sound sources. Every track on both albums is a mix of four to eight tape loops, excluding those with electric organ and synth solos.

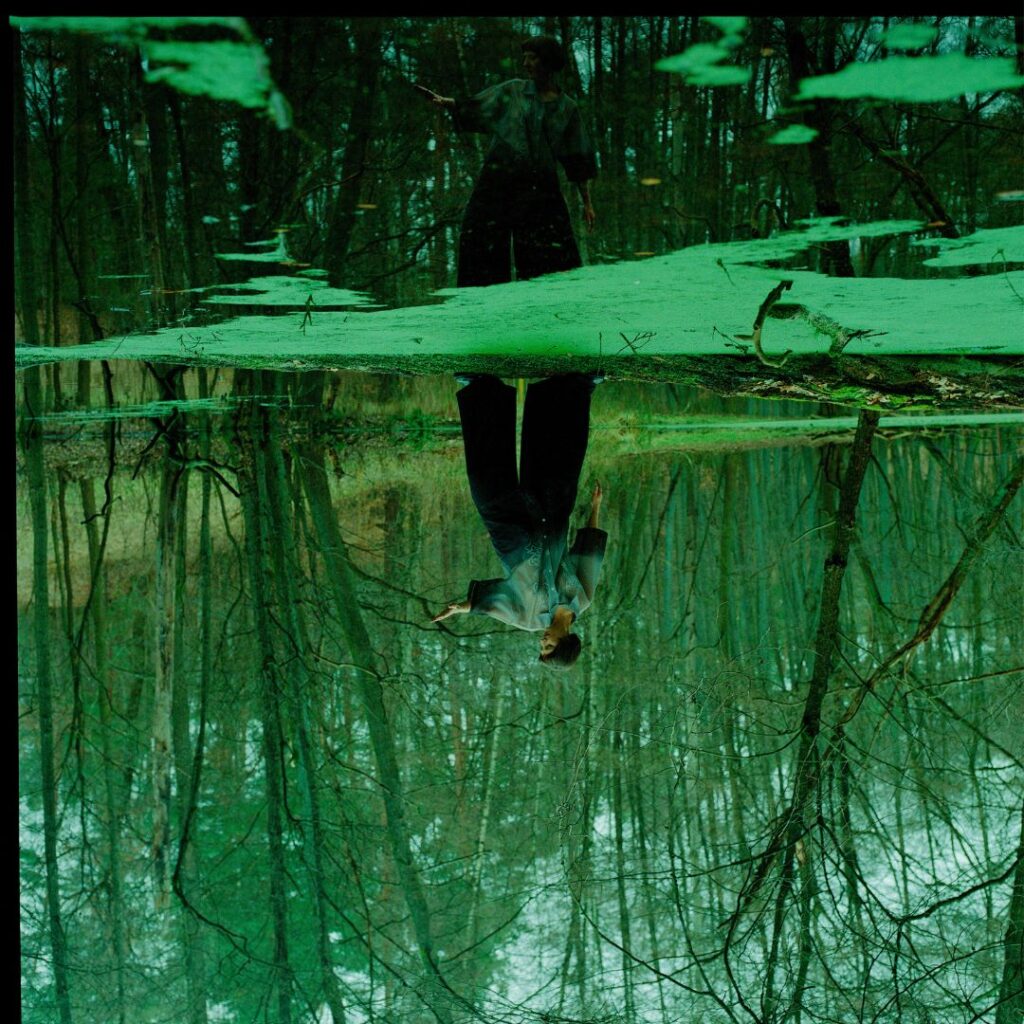

In Nostalgia Por Mesozoica, nothing is real. The album’s cover image of the artificial tropical diorama is a simulation of the natural landscape. It inspired me to create the album using sounds that resemble acoustic percussion and field recordings of birds and animals but are, in fact, synthetic. As for my latest album Meta, I limited myself to two instruments: a metallophone and four-track cassette loops.

What are the most important elements you consider when crafting the sonic texture of a piece?

The first rule I always set before starting any piece is that it must be difficult for a listener to determine the exact period of time when this piece was created. I would say it’s a kind of time-genre disorientation and manipulation game for me, which is very important for the Muscut label releases as well.

My latest album Meta, which uses only the metallophone and a four-track cassette recorder, could, in theory, have been made at any point since the instruments were introduced. This characteristic is applicable to any of my releases, and the resulting approach creates a blend of attributes: haunting, blurry, and a sense of uncertainty in the sounds.

Those sound qualities are captured well throughout your music. What is the most unusual source of sound you’ve ever incorporated into your music?

I generally don’t intentionally record something unusual, but once I was quite lucky. While I was recording random crowd noises and mumbling inside New York’s Grand Central Terminal, there was a guy speaking cinematically on the phone in a very Moodymann style—something about the Bronx. His speech, which I deconstructed into loops, ended up being one of the fundamental parts of my forthcoming record.

Can you share more about your next release?

It’s scheduled for release in 2025 or 2026 under Muscut. Like Meta, it’s going to be non-electronic. It’s an electro-acoustic work featuring numerous tape loops of various instruments and field recordings mixed and matched into the tracks. My trip to New York in 2022 inspired this entire work, particularly the Milford Graves solo exhibition.

Talking about exhibitions, is there a specific project that significantly transformed your approach to music creation?

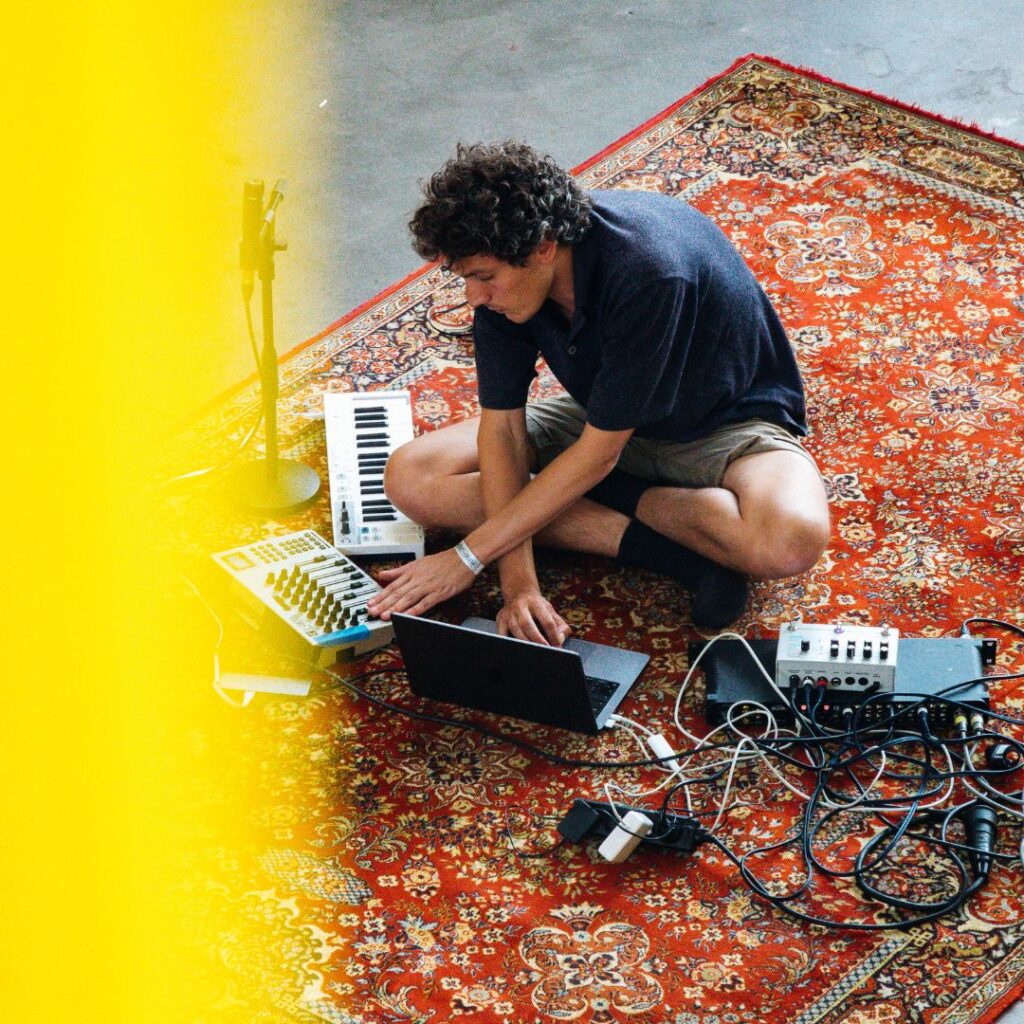

I once saw a concert by the Kharkiv-based musician OK01 in Kyiv in 2006. His set-up was organized on a small, very short-legged table in front of him while he was holding a guitar. It looked like some magical miniature garden with cables sticking out here and there, modified cassette players, audio toys and guitar pedals, and a 7″ turntable with a broken record on a loop. It dawned on me immediately that this is what I was meant to do, and I decided I wouldn’t make music on a laptop anymore.

How do you decide on the theme for a new project or a series of works?

It varies a lot with each album. My first serious LP record, The Sounds of Pseudoscience, was an homage to the Ukrainian film studio Kyivnaukfilm. They were making educational, documentary, and scientific films for schools and universities with exceptionally amazing soundtracks. Unfortunately, their archive was destroyed in the mid-1990s, and nothing was left to release on Shukai except for two soundtracks that we found in the composer’s home archive: Alice Through the Looking Glass and Battlefield. I tried to recreate the mood of those lost soundtracks in The Sounds of Pseudoscience.

In the case of Rings, there was no theme, but rather a technical limitation of using only tape loops as a tool for the album production. This was similar for Meta, albeit the source of sound being limited to a solo of the metallophone. In the case of Nostalgia Por Mesozoica, the theme started with an image, a picture that I took in Kyiv’s Natural History Museum in 2013, which haunted me afterward and prompted me to craft what became the album.

What are some other non-musical influences that have shaped your artistic output?

I was a cinephile during my early 20s and a member of the cinema club in my then-hometown, Dnipro. It was organized by a university professor who held the screenings in the old local planetarium, where people primarily watched hard-to-find French New Wave and Italian Neorealism films projected on a spheric ceiling. I think that definitely influenced my musical taste, or at least, I’ve been collecting lots of soundtracks since then.

Do you work with archival sounds in your own music?

I don’t use archival material in my works. This is part of my game of disorientation for the listener. I aim to create the illusion of using old samples, making it difficult to relate my work to any specific time period. While I do sample and loop a lot, the material is always something I write myself or create with session artists.

What is your approach to selecting artists and projects for your label, Muscut?

I perceive the label as an individual artist or collective with its own concept, aesthetic, and sound palette. It is meant to be coherent and consistent, like a gem or a crystal, with the artists as the edges. My favorite labels are the ones that give the impression that, behind the catalog, there is a single artist making all the music under various monikers, such as Ghost Box and Faitiche. So I try to shape Muscut in a similar way.

And how do you discover music for your sub-label, Shukai?

YouTube is my favorite source for digging, and my most interesting discoveries end up being released on Shukai. The label archives works from the 1960s to 1990s, including Ukrainian films, animations, and music created by outsiders who were banned during Soviet Ukrainian times.

What new directions or technologies are you interested in exploring, both in your work and your labels?

My mindset is to rather reuse and recycle existing resources than to dive into exploring something new. I feel that many people do not fully utilize or simply enjoy all the possibilities and capabilities of any technology because there are always new ones in the perpetual hype rotation. I’m not saying this about all people, and I know everyone has their own style, but this is simply my approach to sound.

As for the labels, I would be interested in audio restoration AI software that could be helpful for the Shukai label. We have a lot of low-resolution and damaged audio files that are not possible to restore with traditional tools, and I would love to bring those to light.