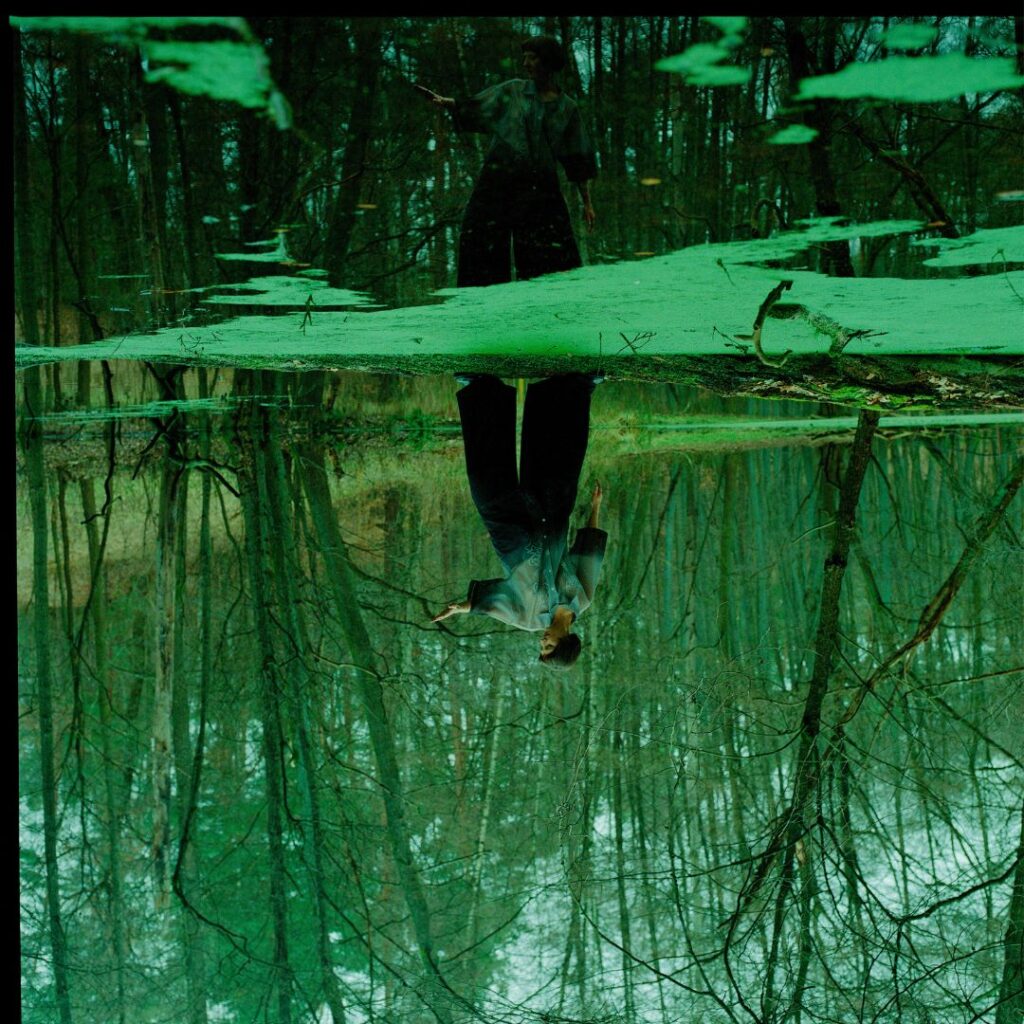

connecting imaginary threads with Alexandra Spence

Seemingly inaudible spaces for Sydney-based Alexandra Spence are places brimming with potential sounds and harmonies just waiting to be uncovered. Her boundless creativity and tender passion for micro sonic universes collectively develop spaces filled with tickling resonances and vibrations. She finds meaning in a practice of careful listening and insightful observations.

As Alexandra is touring now around Europe, we were lucky enough to catch her for a little chat and learn more about her musical journey and main inspirations.

Your latest release, “A veil, the sea”, as well as others before it, “Blue Waves, Green Waves” and “A Necessary Softness,” have strong references and connections to water. Do you remember the very first excitement and desire to record these micro-sounds of a liquid matter?

I guess my answer for that is multifaceted. One is that I grew up going to the beach as a kid and my dad surfs all the time, so we would always take camping holidays at the seaside. It was like a phenomenological experience for me as a child. I remember touching all the seaweed, peering into all the rock pools, and getting dumped by the waves. I think that’s just a part of my life – growing up in Sydney and on the coast – that I never perhaps really interrogated until more recently.

The other bit is that in 2014 I moved to Canada with my partner for a few years. First to Toronto, and then to Vancouver where I instantly felt kind of connected to home because I was on the coast of the Pacific Ocean again, but on the other side. There was this immediate kind of longing for the ocean because it both reminded me of Sydney and was a point of connection to it. It was a coastal city and it was the same body of water. That felt kind of special.

It feels indeed very intimate not just only to record the sound, but also to dig deeper and connect it with the particular land of its origin. Do you consider it as a sonic landscape?

I actually ended up making a work related to that idea in Vancouver, where I started burying tape loops. I went to all of the city’s twelve beaches where I would make a recording onto a tape loop in the location and then bury it in the sand or in the grass near the beach for a period of around three months and have the location degrade the recording. I came back and dug them up and created a work based on these degraded tape loops that were kind of seascape sounds. I liked it because I saw it as a kind of giving up of my own autonomy and letting the landscape affect its sounds. That was the first work I made connected to water and the ocean.

Was this the impetus for using contact microphones in your practice? Were you interested in micro-sounds before getting into these liquid spaces or did the water itself make you feel like you want to dig more into the matter of sound?

I may have started working with it before working with water sounds. I actually got into contact microphones not through field recording, but through installation work. I used them when I was doing my masters in sound installation in Vancouver. I attached them to glass windows and these sorts of things to kind of get the vibration of different outside-inside spaces. Then I went on a field recording trip with Francisco López in 2016 and I think I bought the hydrophone in preparation for that.

In your work you often use daily objects such as toys and dishes to create sounds. I even saw a video of you using the clothes dryer as an instrument! Is it because, for you, the visual world is strongly linked to the sonic universe? Is it because you want the sounds to be seen?

It’s a bit of all of that. I often bring in objects into my performances because I see it as a way of inviting the audience into a performance, or like a form of expanded field recording. Instead of taking the audience to the source of the field recording, it’s taking some of the objects from the location into the concert space as a way of displaying what makes some of these sounds.

Experimental music can be quite alienating sometimes in certain contexts, so it’s a way of allowing people to access the work on a different level. I think the objects have their own history, narrative, or poetry, so it kind of adds another level to the work, as well. When I started out I was very much interested in these inaudible sounds, or sounds that we don’t pay attention to. I still am, but for me it’s expanded to just being interested in vibration, resonance, and the way that sound can make objects, places, and spaces kind of feel alive. Reframe these spaces that we exist in.

For your live performances, do you mostly want the audience to be involved, so they can also feel the vibrations of the space?

That’s kind of how it began with the objects for me. When I did my masters, it was an interdisciplinary program and I did it with people that weren’t necessarily from music backgrounds, but rather from theater, dance, and visual arts. Often when I would present my work, I would get critiqued on the visual aspect of performance, because that was what they knew to critique. It made me really aware of the fact that performance is also a visual thing, as much as I like to imagine it purely as sonic. Lots of people experience sound through images in their heads.

You also often incorporate narration and spoken words into your pieces. What is the purpose of it? Do you treat it as an informative matter or another layer of sound, or by using your own voice you simply want to mark your presence?

It started as just another texture. When I first started using voice, I would kind of whisper or speak really quietly, so it didn’t really matter whether people could understand what I was saying or not. It was more about the voice as just another sonic texture and layer within the work. When I make field recordings, sometimes I’ll say at the beginning of my recording, like where it is or what time of day it is. And then that kind of made it into one of my recordings. I guess I became a bit more experimental when I would do field recordings and sometimes I would talk to the recorder about what was going on as well. That’s how the voice kind of came into my work.

I guess over time I got a bit braver and started to just include it. I realized that people sometimes like to know what you’re saying. So it was just another way of offering information about the work, because my work is often quite layered and there’s a reason for all the objects and there’s a kind of poetry and a narrative that’s tied into it all. It is quite subtle, so I do like to give a bit more context about the concept.

As for the concept, what’s your approach for releasing music?

I think it’s really different when I work on releases. The release I did with Lawrence under Room 40 called “A Necessary Softness” was based on performances. I’d been performing a couple of sets that were quite interrelated for a little while and I wanted to just kind of get them out there. It was a way of documenting that. With the releases that came out this year with Room 40 and Mappa, they were both kind of written for specific instances. I guess the one with Room 40 was kind of like a Covid homework. Lawrence wrote to me and asked if I wanted to do some homework…

Just some really good, well done homework!

It kind of took a bit longer and developed into something a bit different. The Mappa release was a commission for Radiophrenia initially. I don’t know how that came about conceptually. I guess it’s all got to do with stuff that I’ve been thinking about and then it just, you know, seeps into each other and it’s hard to work out where the beginning is and what started it all.

You completed a Master of Fine Arts in sound installation only to later undertake a mentorship with David Toop. How did that experience shape your practice?

It was really wonderful working with, or being mentored by David. It was 2018 and I had around 10 sessions with him. I would just go to his house and we would just chat basically. When I first arranged it, I thought that maybe we would improvise together or maybe he would give me some listening to do. But actually he gave me a novel to read by Dorothy Richardson. A section from that book became the title of my first album ” Waking, She Heard the Fluttering.”

Working with David impacted me in a way I wasn’t expecting. It was more subconscious and subliminal. Just talking with him for hours at a time was hugely influential because he’s a really, incredibly intelligent and interesting person. He kind of pushed me to find my own voice. I think that was the most important part at the time. I’d just come out of academia and I was considering doing a PhD. He really pushed me not to do that and suggested instead that I spend a bit of time just discovering who I am outside of an institution.

I think that was really influential. It made me a bit braver in presenting things, like text within my work or without having to critique everything I do so heavily by an institution. It kind of made me a bit more free in how I presented my own work. Definitely working within an academic structure is also really helpful and pushes you to challenge your work, but kind of challenging yourself on your own terms is also really beneficial.

Was there a moment when you felt like you had discovered everything about sound?

Definitely not. I never know how to say this without it sounding really hokey, but I feel like working with sound has kind of become a bit of a worldview for me. I see things as being really interconnected. When I work with sound, all of my thoughts are really kind of tentacular. Sound is like an imaginary thread that connects all these different things through vibration and resonance. It runs through our bodies and our furniture, it resonates in our lamp shades and these sorts of things. So it’s kind of more – I really don’t want to use the word holistic – just a way of existing in the world. I don’t think that it’s ever getting to the point where I feel like I’ve collected everything. That’s not what it is for me.

So if you could give any advice to people who want to explore sound, what would you share?

When I was first getting into field recording, people would talk about gear all the time. There’s such a gear fetishization within the industry, which is so dumb, because you can just record on your phone. It doesn’t really matter what you are recording on. Obviously, if you have fancy gear, then getting high quality recordings can be really nice, but also it’s not essential to creating good work. Personally I really like working with different materials. Also working with tape and stuff that can be quite accessible and cheap. It’s not about the quality, it’s more about the material experience. I’ve been teaching a course on music improvisation this year and I kind of just structured it all around listening. I think listening is the most important thing.