Constructing Imaginary Spaces with Christina Vantzou and John Also Bennett

A first listen makes it quite clear that the new albums of Christina Vantzou and John Also Bennett embark on a search for musical landscapes that have yet to be discovered. While Christina weaves distant choirs and field recordings of branches and pebbles with mesmerizing synthesizers on No°5, John crafts an almost surreal and imaginative sonic space on Out there in the middle of nowhere with a richness of color and timbre.

Both currently residing in Brussels, we went for a stroll on a not so windy but still sunny Thursday afternoon. They talked about their new records and collaborating with each other, but also about imaginative spaces and birdsong.

I came across an interview with you, John, where you talked about experimental music and noise and how it all started for you. What’s it like looking back now, from the point where you’re at?

John: I took music lessons as a kid, starting with the piano. I come from a pretty artistic family. My father is an experimental poet and my mother is a visual artist who also plays the piano. They both worked day jobs, but writing and art were always primary. There was always a substantial amount of music playing in the house, from avant-garde to classical music and just music from all over the world. Anyways, I had to take music lessons. “Practice your flute, John!”, but it wasn’t like “you’re gonna be a musician.” It was just part of how they wanted to raise their kids. So I took piano lessons and for some reason I wanted to switch to the flute at some point, and I did that for several years. Eventually I switched to saxophone and later on I picked up guitar.

Christina: How long did you play sax?

John: I took lessons for a couple of years, but it felt like a natural progression from flute because they’re both in the same family of instruments. I had to practice every day for half an hour and I remember really battling against them.

Christina: I used to babysit and the “I don’t want to practice” sentence came up quite often.

John: Yeah, you had to practice and as a kid you don’t want to have to do something, especially coming from your parents. But I did practice most of the time and developed some technique. To this day, I can generally, if I put my mind to it, figure out any instrument. Except for brass. I was never able to play the trumpet. I could not get the blowing right. Eventually I switched to guitar because I was getting into rock music.

In high school, I was in a rock band and we were moderately, reasonably successful in Ohio. We won the talent show, the battle of the bands, we opened up for Blue Oyster Cultand a couple other big rock bands, and we even played on the Warped Tour.

Yeah, I saw some pictures of those times.

John: You found some? You really did your research! I’m actually quite grateful because it was just before everything was on social media, so you can’t find that much evidence online. But we had a good time and learned a lot.

As that band reached its peak, I got into more experimental music. By the time we graduated high school, I was basically fully into noise music. There was a lot of that going on in the Midwest at that time. It was a really cool time for that scene.

At that point, I really abandoned song structure. It took a while before I got to where I am now. I was working through some sort of existential dread at that time, so a lot of that early stuff is pretty harsh, kind of self-destructive. I was playing shows with this giant industrial fan that I found in the warehouse I was living in. It was just this rusty hunk of junk. It was fully exposed and I would plug it in and the fan would keep going while I tried to stop it with my hand, and I played the flute through it to get that natural sort of tremolo effect. So it was this very physically dangerous performance but it actually planted the seeds of where I’m at today, that is playing with these electric tones and flute.

Hearing this makes a lot of sense because one of the last tracks on your newest album, Embrosnerós, really felt like this question and answer between synthetic, electronic sounds and acoustic elements.

John: What I’m doing right now is using acoustic or organic sounds to trigger electronic sounds. So that piece, Embrosneros, is a lap steel guitar triggering a DX7. I guess I like that. For one thing it’s convenient, because I don’t necessarily want to play live to backing tracks. I’m playing solo, so it gives me the opportunity to play several instruments at the same time. It’s a customized system that I can control the parameters of, but I also like that I don’t know what’s gonna happen 100 percent of the time. It keeps it interesting for me. It leads to stressful soundchecks but it keeps it more exciting. There’s always this organic element that I don’t fully want to get rid off.

And, Christina, how has your background shaped your musical language?

Christina: I didn’t have a formal musical education like John did, but we did have a music class twice a week in elementary school. I went to art school in Baltimore where I got a degree in the Visual Arts. A class on sound recording gave me a handle on some basics. The rest of my music education came through DNA.

The Greek part of my family comes from Epirus with a very strong musical tradition, where families form ensembles, and are known for a very specific style of playing their instruments and using their voices. My great-grandmother participated in the practice of lament song. When I learned about this family history, I felt like I finally understood where my interests and approach to music stems from.

Listening to both of your music, I get this sense of a certain otherworldliness. As if it’s not happening here at this very moment.

John: I think that’s part of it. With my albums, I’m often hesitant to use a photograph as cover art. I don’t necessarily want to tie the music to a real place. I tend to prefer gestural drawings that are evocative of something, but not necessarily something specific. Just to trigger ideas. Music for me is really about visualizing these imaginary spaces, speculative spaces that maybe don’t exist, which don’t have defined boundaries. It’s more about this feeling of a place that could or should exist.

A lot of the time I listen to music wanting to find something. And when what I’m trying to find isn’t there, that triggers me to try to make that music. That’s fully the case with the new album.It started with driving through the American West and just being surrounded by these vast surreal landscapes. When you get out there, you really appreciate the scale of the continent and the beauty of it. My brother and I were listening to a lot of country western music on that road trip. That music is incredible but it just wasn’t quite translating the feeling I was getting from these landscapes, which is like this vast, surreal emptiness. So the idea for this new album really started from that specific moment, that specific place. But I ultimately didn’t put a photo of the landscape on the cover, because I didn’t want to tie the music to that particular place forever. I’d like for it to have its own life, for listeners to put it in their own places.

Christina: Your question makes me think about imagination and the escape that music can provide. It also brings to mind what Saidiya Hartman calls “a practice of possibility.”

Surreal Presence on No°5 is dedicated to Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten. I listened to, and read their work so much these last years, and am always struck by the depth. Hartman’s work to re-imagine the lives of black women in Philadelphia and New York at the turn of the 20th century in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments helped me to be more conscious about the urgency of this practice.

I strongly feel this is what the world needs right now: to think of, and dream of, and act in accordance with better systems of how to live. There’s something very meaningful, something much more profound than any individual goal, to just engage in that kind of thinking. I feel like music is a really positive tool for navigating imagination, and for shaping reality into something more liveable.

Field recordings are quite prominent to both of your musical practices, almost working as a sound documentary.

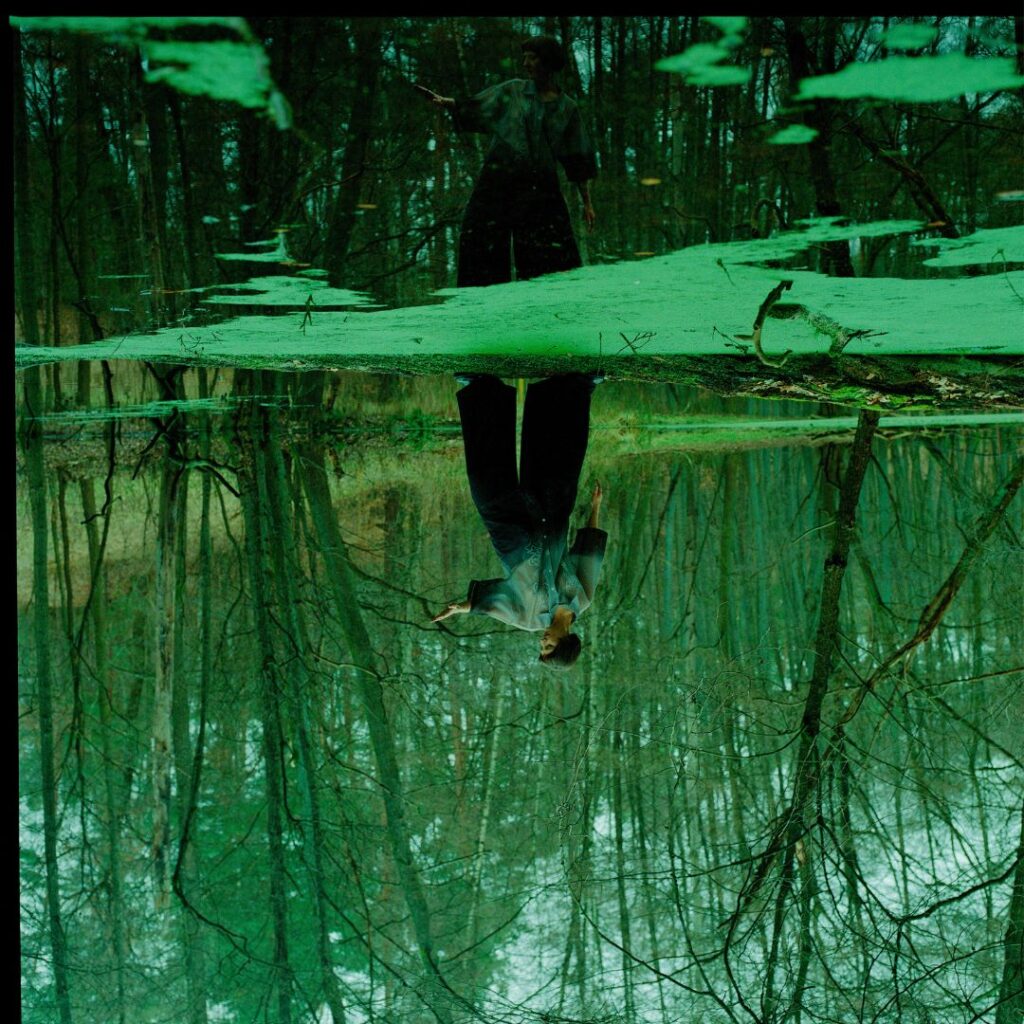

Christina: More and more, yes. I’m all for field recordings. John and I also talked about making two versions of an album: one with field recordings and one without. Just imagine you’re walking in a forest and you can choose to let the forest provide its own sounds.

Field recordings have a really transportive quality. They’re powerful and subtle at the same time. Traveling is also a really important part of our process. Field recording equipment is small and easy to transport, so we tend to always have a recording device with us. Some recordings happen so spontaneously that they become part of that particular charged moment. It’s nice to put things like that on a record.

John: Lately I’ve been a little unsure about using field recordings in my solo music. I want the music to be able to live in the sonic spaces that people are listening to it in. If you add field recordings to a piece of recorded music, when it’s played back you’re putting environmental sounds into an environment that probably has its own environmental sounds. And for my new album, I really wanted for people to be able to play it in a place that has its own sounds and to let those sounds color the atmosphere along with the music. I really like the idea of music that can combine with and complement natural sounds in different environments.

The more common use of field recordings is also fascinating, because it is categorized as non-music.

Christina: Yeah I’ve heard that, but then again, there’s this thing of trying to categorize and label something. It makes me think about who has the right to say what is music and what is not. A lot of music stems from listening to nature and it’s probably the major source of what we call music, so why call nature “non-music”?

John: What do you define as music?

Christina: For me, sound and music are on the same spectrum. They’re not separate from each other. What if a field recording has birdsong in it?

John: But what if the birds are simply communicating? Do the birds see this as singing, somehow elevated from “non-music?”

Christina: Difficult to say, but I’d say music is not just in the human domain, and there can be musicality and style in simple communication.

John: I totally agree with that. I’d just add that as humans, we have this ability to listen to any sound and label it as “music”. But it really is just sound. Vibrations in the air. In the case of nature, there are so many different and amazing examples of communication through sound. But if we want to call it “music”, we can. What is music and what is not all depends on your own experience.

How is it going with your goal to achieve N°9, Christina?

Christina: Still very much a goal, yes! These three thoughts: “I can make a record”, “It will be a series,” and “It’ll run through 9” came to me all at once. I just have to keep balanced enough to live it out. When you have these kinds of ideas, they live inside you pretty deep.

How does composing for yourself differ from working on a compilation with other labels?

Christina: When someone reaches out with a certain purpose or requests one track to support a good cause, this specific request is very different than creating a whole album’s worth of material. Although, sometimes someone like Lieven Martens reaches out to request a full album. He is great to work with because he runs a label, and he’s also a musician and composer himself. It was such a healthy process making Multi Natural. I definitely shifted more into field recordings, thanks to that invitation. Sometimes it’s good as an artist to be steered in a new direction through an interesting invitation. To steep yourself in a creative process, feel supported, and not be pressured in any way.

John: I was really happy about that Multi Natural record because I’ve been encouraging Christina to do something outside of the N° series for years.

Christina: Yeah, that’s true. John helped me realize that there are other ways and other paths to go down. The numbered records do take a lot of energy to realize, so Multi Natural was a nice contrast. A much lighter process in a lot of ways.

You also collaborate with each other on albums. How do these come to life?

John: It is evolving as we move forward, for sure, but it’s always been a spontaneous type of collaboration. I’m a little less self-critical and self-analytical during collaborations. It’s not all on me, so the load is spread out a little bit. And both of our energies become something that’s just outside of one’s self. You have somebody else to bounce sound and ideas off of. We also share music constantly, so we both know each other’s musical sensibilities so well.

Christina: We both always work on and make music, so it feels very natural to make music together. We live together and know each other’s work really well. We hear each other practicing. This means we’re involved in each other’s work in so many ways. The preparation happens really naturally. For a N° record, I can spend one or two years getting prepared to work with an ensemble. With a collaboration, you can walk into a space, agree on a timeframe, and just go. With John, we often just set up and jam.

Pictures by Natasha Pirard, John Also Bennett, Elvis Fontaine-Garant, Megan Bruinen