embracing dualities with Pernille Meidell

Gently observing the ambivalences of everyday life, Oslo-based Pernille Meidell aka Perimeter O examines the boundaries of perception while searching for unique narratives and forms of expression. Torn between the visual and audial worlds, she finally decided to merge them together in 2019. That’s how Breton Cassette came into being – not only to bridge this gap, but also to create a space for sharing ideas and realizing them through boundless explorations.

Although she usually prefers to hide behind the scenes, she made an exception for us and confided in us about where she finds her comfort zones and why she used to sing to her sculptures.

Let me start by saying that I only discovered your music recently through Radical Tenderness and asked myself…. Why didn’t I know you before?

I like operating on the outskirts. I don’t fancy promoting myself. I don’t like these kinds of things at all. It’s a world that I don’t feel comfortable in. Actually, it was the same with the art world. Breton helps me to be a part of it, but I like to have this space between me and what comes out. It allows for this personal attachment that I can’t afford to have with my music. It’s a very sensitive matter for me. Sometimes I even think it’s better to just make it, but rather have no one listening to it! There is this really strange mix of I want to and I don’t want to.

So is that why you prefer to hide behind the moniker, Perimeter O?

That’s partly why I prefer to hide behind it, yes! This name came up when I was working on my album called Inside Outside. It was around the time I started Breton. I wanted to try to at least sort of create a line between that project and my own. So in that way, I wanted to take a moniker and also try to give it a bit more distance. A perimeter is a measure of a contour. It is an outline, while the O is the symbol of a circle.

If you have a contour or an outline or a circle, there’s always an inside and an outside, right? I think a lot of my projects are about this possibility of going in and out. Another way I think of it is more from a micro and macro perspective, where you have something inside, but there’s also something that you have to relate to the outside and the opposite way. You can sit, read a book, and be in your own world, and then you can look up and look out at the world, and you have to relate to it somehow.

I think that this back and forth relationship is very difficult. In many ways, it’s based on fear for me. I think it is very frightening! I’m struggling with this shift. I’m trying to work on it and practice. The circle can be comforting if you’re inside it.

It’s very interesting, especially since you come from a visual arts background. You’re always sort of inside and outside. In Breton, you’re part of the process of creation, but you’re also the creator. That makes you both inside and outside the process.

A lot of life is actually about that. We also have an inside and an outside, as individual human beings. This duality interests me a lot.

So how did you get interested in music?

I think it actually has a lot to do with the fact that my brother was in the boys’ choir at church. He sang a lot, both at concerts and during services. I remember sitting there listening to those psalms amidst that sacred atmosphere, that melancholy. I think it really struck me and somehow comforted me. I remember wanting to be one of those boys! I wanted to sing! I think that’s when I first felt that I wanted to make music too.

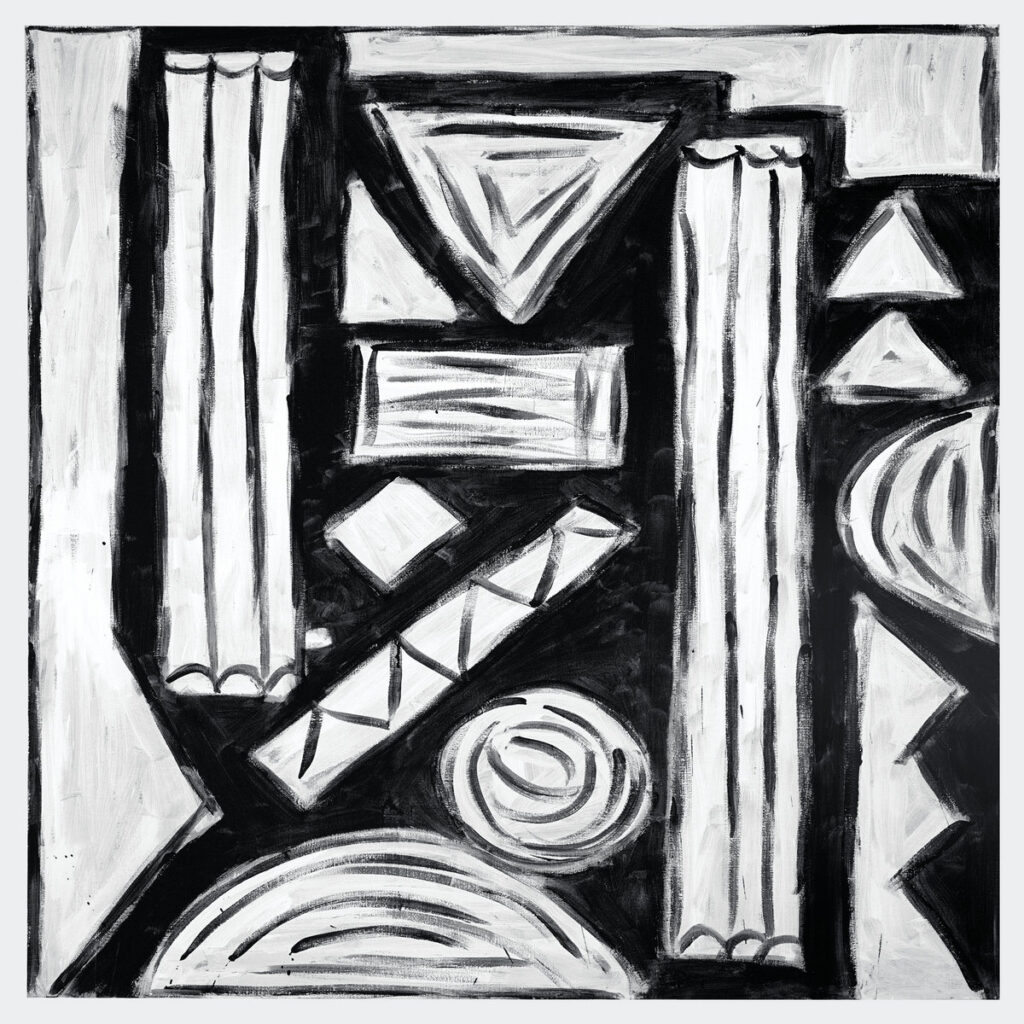

Music can make you feel compassion and it can make you happy. It can comfort you. I think that’s what I was missing after doing sculpture for a while. I wanted music to come into my art in a way. I started singing to the sculptures, in a performative aspect. It’s a bit embarrassing…

No, that’s pretty wonderful!

Well, it’s kind of an effort to try to transfer what I felt with music and how it responded to me. I tried to transfer that into the object in a way, because creating them has kind of become dead to me. Just like that designer item you see in the window when you walk past a fancy shop.

The objects are also very material, and the music is sort of out of sight. Did you want to breathe this atmosphere into the object in this way? To combine the visible with the invisible?

It’s a bit of that shift between the abstract and the concrete. You have an object that is very concrete in a sense. You can also fill it with meanings, but it’s there. Then the music is a bit more associative, at least for me. That shift between one thing and another made me want to broaden that perspective, to breathe some life into the sculpture.

It seems like from the very beginning you wanted to make everything yourself. You debuted in 2017 with Blueboy and in 2019 released Inside Outside under Breton Cassette. Why the need for independence?

There is both a positive and a negative feeling around that. The positive one is that I have ownership over it. I have full control over the whole thing. I’m the one putting it out there and I’m also in control of what I’m doing. I know that all the decisions I make are made by me and that they are in my hands. I remember it was like that with the sculptures I made. I didn’t want to sell them because I didn’t want anyone else to have them! That’s a bit of what I think about when I say I don’t want people to hear my music, because obviously I want to release it, but I don’t want to be misunderstood either. It’s a very strange mix of feelings. I think it has to do with the fact that I don’t have the distance that I should have. It just feels too personal. But it’s also problematic because maybe I have a disability in trust? You have to find someone you really trust, and that’s very important to me. In many cases, I think it’s difficult to find that person.

But at the same time, doesn’t that put all the trust in you?

Exactly! You create something and you probably don’t even realize that someone will listen to it. You don’t even realize that someone will care. I have this thought all the time that no one else will release it, so I have to do it! I have to do it myself.

You say you prefer to stay on the outskirts and your music indeed has a mysterious quality to it, but often there also seems to be little particles of light behind it. How has your music and your approach to sound evolved?

I think it’s always a bit of a two-sided thing. With the start of Breton, I’ve become a more active and present listener because I get a lot of demos and things to listen to. But how it’s also evolved is that I’m aware that you need to make room in a certain way. I need to make a mental room for me as a listener. I’m an emotional listener. I need to create a mental room for myself when I listen to music. Often it’s an opportunity to create a room to collaborate, to work with other people. Sometimes it’s also more of a physical room, like the boxes from Breton. You open them and then you have a physical thing, a little handy thing that you can open, and there are more little things in there.

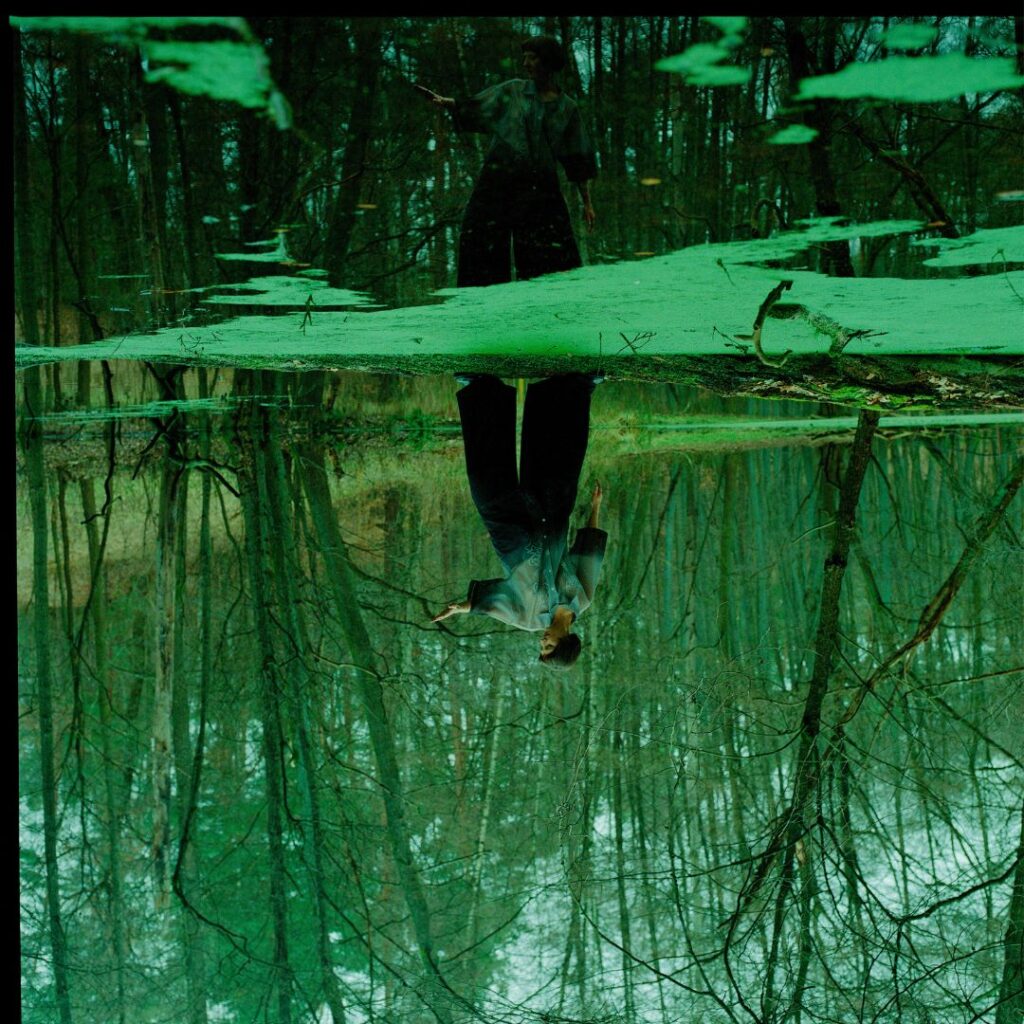

Over time, field recording has also become important to me. I’m very excited to be taking a course in Edinburgh in the summer called Murmuration. It’s like a week of field recording. I think there will be 20 people there and we’ll exchange ideas, make recordings, and just spend time together. I think that’s going to be very nice. It’s kind of that awareness and better active listening that also shows the potential of field recording.

Is nature something you feel you can draw inspiration from? Everyday objects, everyday sounds – do you feel they have potential for you?

Yes, absolutely. I think nature is a very strong inspiration. It’s kind of an open space, that’s how I see it. I also like the fact that it’s uncontrolled. You record things and then you put the recorder down and when you go back into the studio you suddenly hear things that you weren’t aware of right then and there. Each time it’s such a surprise.

Like you said, nature is uncontrolled, but I’m very curious about your working process. Is it structured or is it more spontaneous?

It’s very tiring actually, because the process is very chaotic and organized at the same time. I would also say that these are two necessary parts of it. Quite often it’s based on the experiments that I do. I never have a plan, but sometimes I try to have one. I write down on a piece of paper what I’m going to do and then at the end of the day I do something completely different. I forget the notes and don’t even know where they are. This is both a good thing and a bad thing because I like the flow and it gets me into it. I’m playful and happy about it. But the problem is, how do I do it again? I can’t do it because I can’t remember what all the stages were. I can’t remember what I was doing! This is also one of the reasons why I can’t perform. I don’t have the courage because I don’t trust myself at that particular moment. When I’m recording, everything just happens and I think it’s going to be hard for me to get into that flow again when people are looking at me.

It’s very interesting that you prefer objects and music to speak for themselves. That’s what happens with Breton, isn’t it? The sounds always seem to be closely connected to the visuals, like a symbiosis that complements each other. It’s not just a project, it’s a way of telling a story.

When I founded Breton in 2019, I did it mainly because I felt that this kind of platform was missing. I was a visual artist who also happened to work with music. There are many of us who do that, who use sound as a material in the same way as using plaster, fabric, wood, or whatever. I myself had the experience of falling between two chairs because I am not a musician. I would never call myself a musician in a sense. I’m not comfortable with that, but I’m not comfortable in the art world either. I’m trying to find that space or platform where we could make, almost so-called, sound publications, that both show the artists’ visual and audible interests.

How does the collaboration and the creation of this story usually work between you and the artists?

Mostly I want to meet people in the real world. I’m not only interested in the music that people make, but I also want to get to know them. We listen to music together, but I never want to step in and correct the process in some way. I would never say that the piece isn’t good enough, but it can be discussed. The artists I work with obviously always have the final say.

What I do on my part and what I help with is the packaging of the cassette boxes and the stuff you put them in. It’s all handmade and I mostly do it myself. It’s a need or a desire to create an object that somehow shows both my visual and auditory interests. There is an absolutely strong intention to bring the two together. Sometimes it happens that the artist doesn’t want the object to be included, but then we try to make the J-cards a bit more special. There is always a personal touch to them. Because things are handmade, it’s also important to us that the print run is small, like 20 or 25. I rather want to go for uniqueness than quantity. I always tell the artists what the process will look like and what Breton is in the first place. Everyone needs to be comfortable with that.

If you come from an art background, you probably have this curiosity or this interest in unique objects. It’s like a painting is not painted a hundred times, right? It’s that uniqueness that connects with what I really admire. It also seems to be necessary with a lot of objects out there in the world.

Is that the reason why Breton Matiné came to life–to bring people together? Can you tell more about this series?

I was invited to have an exhibition at the Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. It’s a really nice artist house and they have a lot of good exhibitions. Since I started Breton, it’s been the pandemic, and none of the performative aspects of the project were shown at all. That was a really nice chance to organize Breton Matiné during that exhibition. I made the program and almost everyone featured on the label participated. Some of them simply couldn’t because of the distance, but I gave everyone the possibility to show their project in a way because it felt just so right. That was a great time and it was a lot of work, but also it had a lot to do with the project itself. It’s about meeting people, hanging out together, sharing ideas. I really enjoy it because it’s a nice balance between doing my own things and doing things for others.

How did you feel when the cassettes became part of the exhibition? Would you call them an art object?

I would absolutely say that the cassette is an art object. It’s a very beautiful thing, even just to look at. I have a lot of associations with it from the 90s, when we used to make mix tapes as a nice thing for ourselves. The beautiful thing about it is that it’s handy and it’s small. It’s something you can relate to. I really like that. It’s also very mysterious, because like, how can a magnetic band play music?

Yeah, that’s always the question that I ask myself!

Well, it’s also about unpacking it, which you also do with a CD or an LP of course, but how you unpack a cassette feels so unique. First you open it, then you unfold it, and then things appear… It’s like an object to explore. It’s something that you can read, that you can look at, and then you can listen to. I think it’s a very beautiful thing.

As we are talking about cassettes, are there any exciting projects coming soon under Breton?

The whole year is full already and 2024 is starting to fill up too. I have started to work on the three next cassette releases.

One is with Estonian musician and photographer Liis Ring. That will be a very beautiful little booklet that she’s making with photographs that she’s taken. The content of the cassette is more field recording, diary-vibe in a way. The next release coming up in March is a bit different, because there has been a lot of musicality on Breton lately, like a lot of music-music if you understand. It’s a collaboration with Swedish writer and artist Henning Lundkvist and British artist Tris Vonna-Michell who also works as a professor at the art academy in Oslo. It will be more of a spoken word release, so it’s tipping a bit more over to art again. That’s the way I try to think a bit when I organize the program. I want it to be a little bit of everything. In June, I’m really looking forward to working again with very talented and good friend Elina Waage Mikalsen. She’s a Norwegian-Sámi artist and is doing a lot of sound work and we will make a new cassette together.

The release with Liis Ring is actually a collaboration with another cassette label called Canigou Records. This year, I will try to work a little bit more in collaboration with other publication houses or cassette labels. I’m also exploring more dual work with duos, so it will be like a collaboration with a collaboration.