Harnessing creative energy with Slowfoam

Dreaming in “what ifs” and tapping into the power of collaborative magic are at the heart of Berlin-based sound artist Madelyn Byrd’s practice. Also known as Slowfoam, they emphasize the importance of play in channeling creative energy, while their natural inclination for collaboration highlights what arises when we seek connection outside of ourselves—and all that we can achieve together.

We feel optimistic after speaking with Slowfoam. They remind us that infinite possibilities exist out there, and also within each other.

A lot of your interdisciplinary projects focus on collaboration. What role does it play in your creative process, and how do you determine who you want to collaborate with?

The process of deciding who to collaborate with is pretty organic. Sometimes I try to be more intentional and conceptual regarding whom I want to engage with in the creative process or who inspires me at the moment. But it’s also just my way of connecting with old friends and different people. I like to dive into other people’s worlds and see what we can come up with together. It’s never about the end product as much as the process itself.

Have you always been anchored in a collaborative approach?

I think it’s always been there. I used to play in bands and have always loved sharing creative processes, and during the pandemic, it became a way to stay connected with people. Now, it’s simply the way I want to create, and I hope to continue moving exponentially towards collaboration.

What appeals to you so much about the idea of collaboration?

I think collaboration is a way to dismantle capitalist notions of the brilliant individual artist, making yourself less the focal point. Instead, creative energy becomes the focal point.

In a way, you’re just capturing the creative energy that’s always around, right? It’s not ego-driven. And the more people you involve, the less it’s about you, and the more it’s about the energy that comes through.

Do you have certain practices or daily routines to help open yourself up to these creative energies?

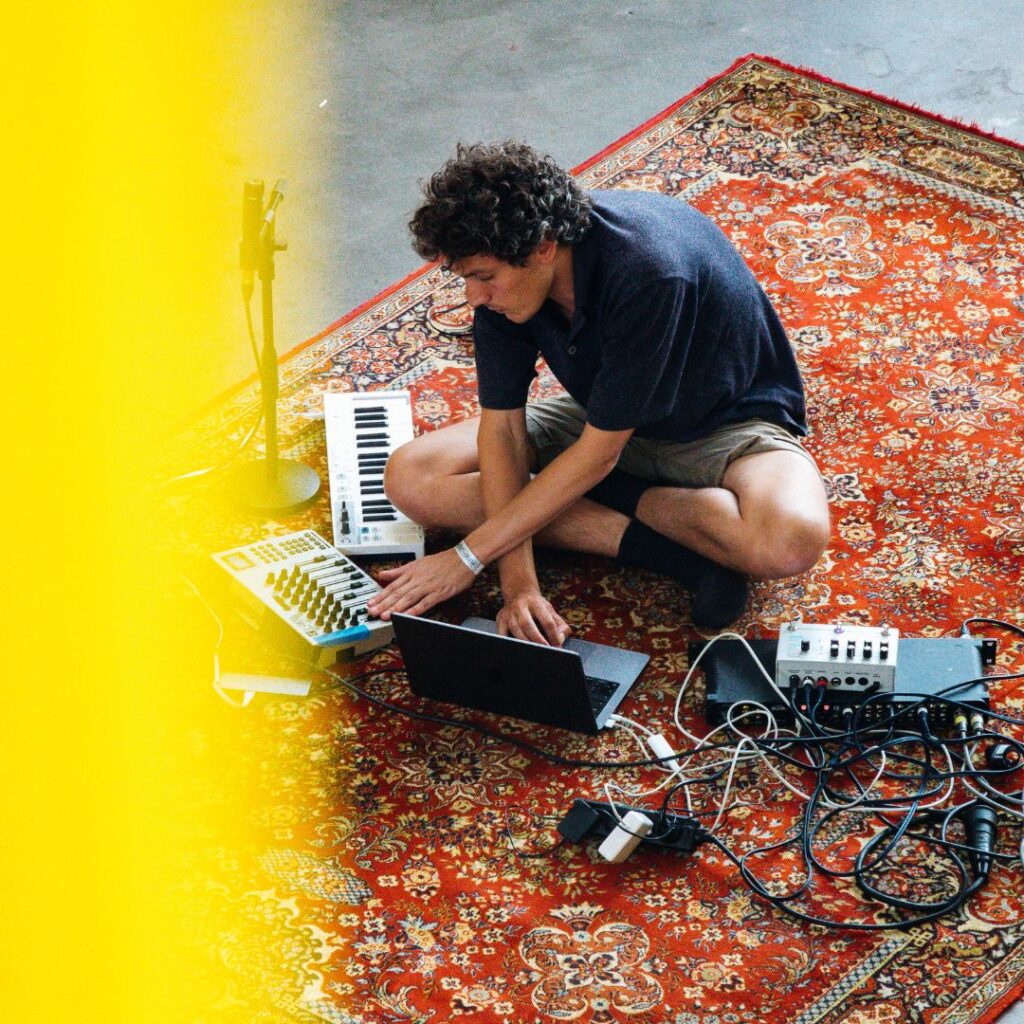

When it comes to my own micro-creative processes, I like to create a flow where I’m not attached to any specific outcome. I write and doodle every day, and lately, I’ve been working on a sketch a day in Ableton—just playing around for about an hour and making music with no set plans. It keeps the creative process light and fun. It’s easy to get bogged down by the end goal or the need to make an entire album or prepare a live set. Having these small, daily tasks helps me keep creative energy free from pressure or weight.

You’ve studied creativity rigorously in your degree in neuroaesthetics. What is neuroaesthetics, exactly?

Neuroaesthetics is the study of the neuroscience and cognitive mechanisms behind any aesthetic experience—essentially, the psychology of how we perceive art and creativity and what’s happening internally during creative, aesthetic experiences. It’s a very broad and new field.

How does your background in this field influence your approach to sound design?

I think studying neuroaesthetics deepened my interest in the perceptual experience. Especially when finishing an album with the listener in mind, I love playing with dynamics—making people feel uncomfortable, or building towards a release in the same way that DJs build momentum before a drop. Understanding what’s happening internally, emotionally, perceptually, or sensorially for a person influences my work.

Since studying neuroaesthetics formally, though, I’ve been trying to counterbalance a year of thinking very scientifically. In response to my program, where everything was empirically driven, I’m now purposefully doing things “the wrong way” to shake myself out of a pretty rigid experience. Not to say that it was an entirely negative experience, but throughout the program, I was craving creative freedom. I imagine what I studied will come back into my work at some point, but right now, I’m leaning into the chaos of play more than ever before.

And were there specific findings from neuroaesthetics that really stand out in your mind as surprising?

My dissertation focused on connection and the impact of collaborative creativity on our felt senses of connection. The most exciting finding for me came from measuring connection in three ways: connection to self, connection to others, and connection to nature. I had participants undergo both a collaborative creative exercise and an individual creative exercise, and actually, the collaborative exercise increased participants’ felt sense of connection to self, others, and nature.

That finding further deepened my belief that collaborating and engaging in imagination and creativity together is incredibly connecting and healing—not just to each other, but also in terms of our connection to the world, the planet, our environments, and ourselves. We actually feel more connected to ourselves when we create with other people.

That gives me goosebumps to hear!

I get that—it’s really reassuring! Especially when it feels like society is becoming more isolated in many ways, I find it comforting to hear that science proves the opposite is true. As we’re being driven further apart, disconnected from the natural environment, and having less time for ourselves, we also have less time for community. I think it’s really important to resist isolation and remember that connection is critical for both our well-being and the health of the planet.

In terms of connection with nature, you’ve often explored the intersection of technology and nature in your work. What drew you to these themes?

I love being surprised by technology, especially when it—whether intentionally or accidentally—mimics nature. You’ll have field recordings that sound kind of technological, and I find it fun and intriguing to sonically abstract these two entities.

In some ways, technology is also natural, right? It’s an extension of us, made from materials from the Earth. And while it’s certainly been used as a tool for evil, it also offers ways for us to connect to the planet, heal the planet, connect to our own intelligence, and understand ourselves better.

How does this interest in nature and technology play out in your choice of sound components, whether organic or digital?

There’s an ephemeral quality that emerges when using technology randomly or chaotically at times, and when combined with an organic sound, like a field recording, there’s something about the two together that just makes sense emotionally. It feels like they’re coming from the same place. I don’t know exactly where that place is, but I think it speaks to a greater creative or emotional energy, and it’s a way of trying to find the relationship between the two not as being separate, but coming from the same source.

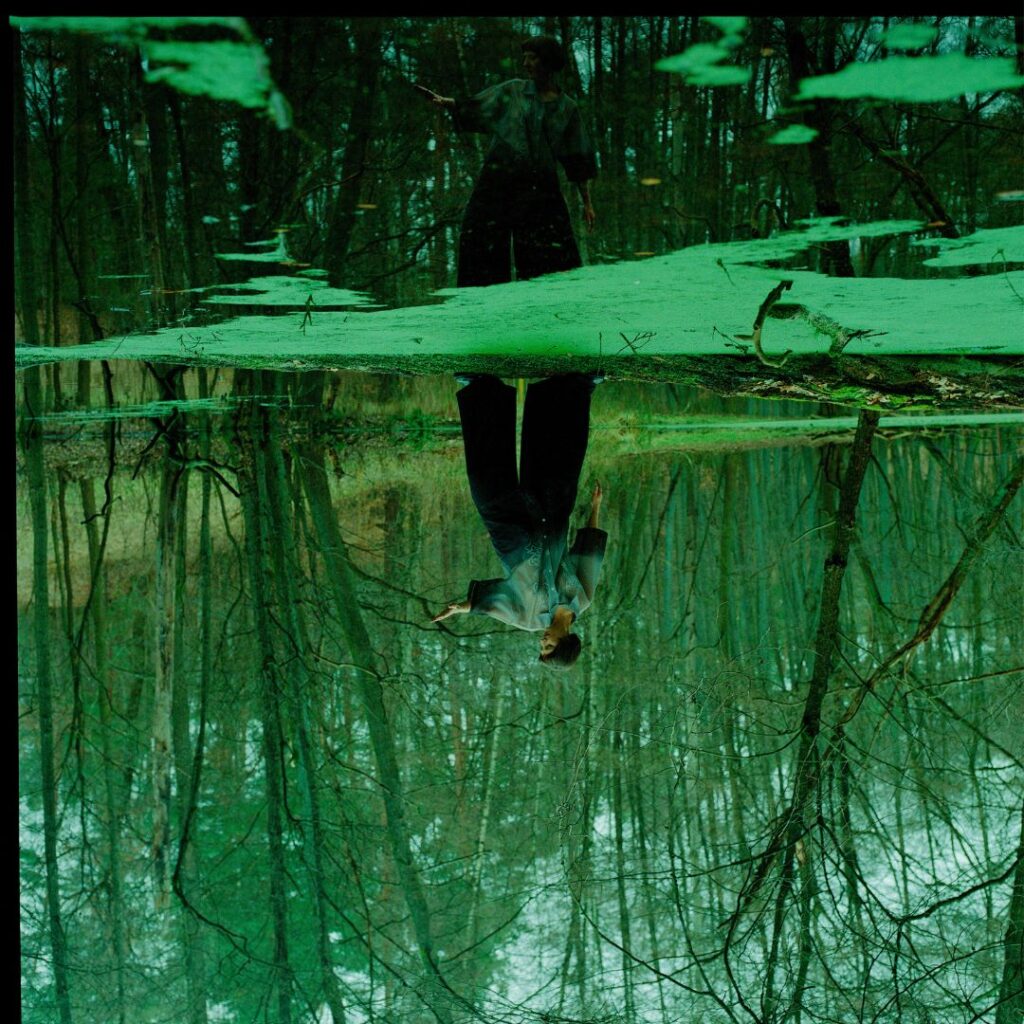

A common motif in your work is water. How does the concept of water inspire your production process?

My approach to sound is very fluid, always shifting and moving. Sometimes, when I’m working on a sound and playing with it so much, it feels like it almost drifts away and becomes something else. I try to stay open to that process, treating sound as a fluid, moving entity.

What message or experience do you hope listeners take away from your music?

I hope they feel a sense of a dream world—of connection and possibility. And that things are possible, the world is weird, and so are we.