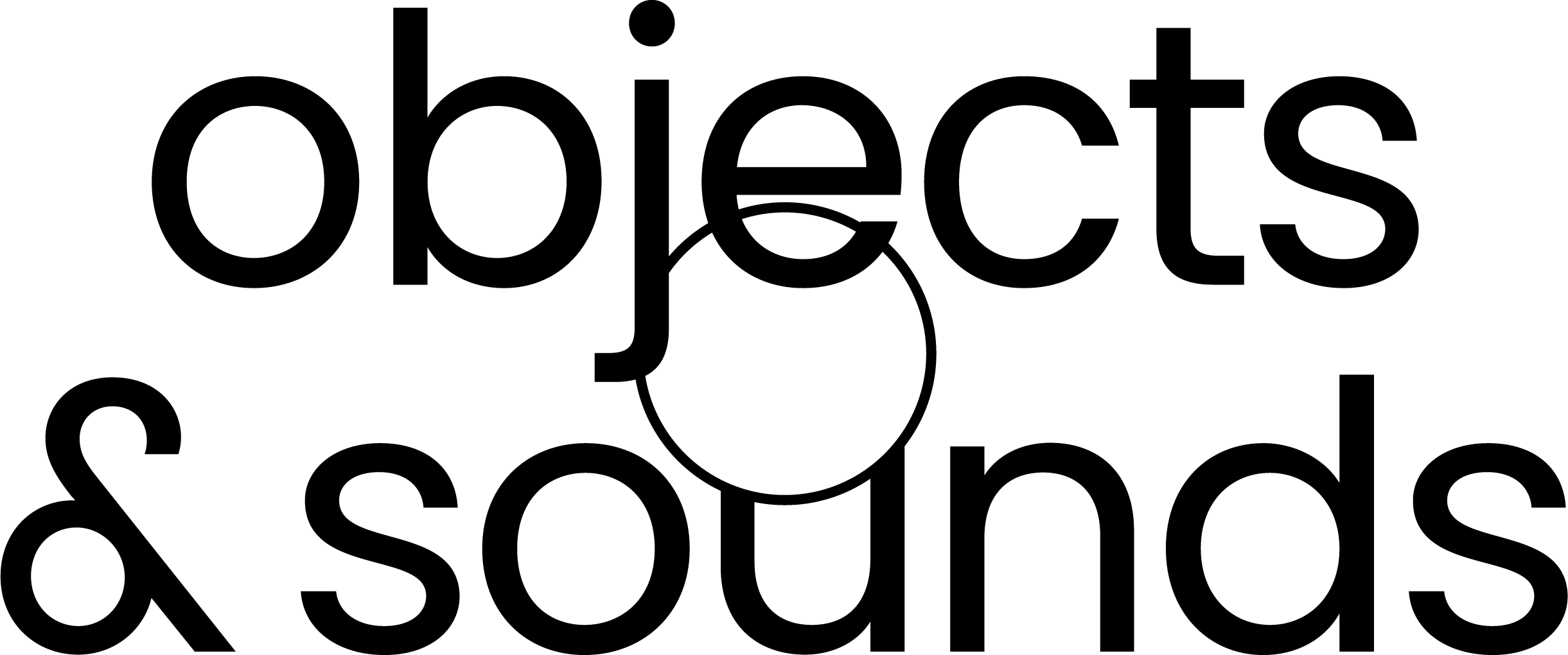

taking snapshots of time with Celia Hollander

Celia Hollander is a Los Angeles based artist and composer working with audio, scores, performance, installation and text. In her most recent record, she works with an assemblage of field recordings to intuitively form temporal experiences. She drenches them, layers them, reverses them, and mostly seems to have fun manipulating them to no end.

Intrigued by her fascination for space and time and also her ongoing list of questions, we set out to have a chat with her to have a glimpse into her unique approach to music making.

How have you kept yourself busy these days?

I’ve been spending more time outdoors. I’m an avid hiker and I love going to the mountains and backpacking, so I’ve been taking the opportunity to get out.

I’ve also been making a lot of music. Although for at least the first month of quarantine, I didn’t make any music. In the last three years, I’ve been working on so many things non-stop that it was actually really nice to not make any music at first. I drew a lot then, but drawing is musical for me too, because the whole point of drawing is to listen to music.

Are you working on any new releases or just making music that resonates?

Before we get into that, can you first tell me a little bit more about what you guys do?

We started an online record store during the lockdown with a focus on moods, instead of genres.

That’s really interesting, especially right now with so many people accessing music by mood through things like Spotify playlists. I think it opens up a lot of possibilities for music to be understood, categorized, and then accessed differently.

It’s also a very-post Internet approach, because what is “genre” really these days? There’s no defining “genre” of our generation. It’s a mix of everything, so we need to approach this hierarchy of categorization differently.

Now that you’ve mentioned Spotify, how do you approach your relationship with digital music culture?

I used to have a physical collection of tapes, records, and CDs. When I went to college, my parents also moved. I packed up everything to either go with my parents or along with me to undergrad. At that point, I decided to stop collecting physical music objects.

That was a long time ago and now I have hard drives of music. I saved all of my music and downloaded MP3s since high school. I’m more of a digital music collector and in many ways that’s physical too. It takes up space on the computer and it also has a physical footprint.

I’m also very much a digital audio producer, so I do feel a strong love for digital music as a medium. Both in consuming it and producing it and where those two overlap.

How did you start making your own music?

I started playing music as a kid. I was very lucky to have piano lessons when I was younger. I first started playing classical piano and then I joined the jazz band when I was in middle school. I started recording my own music on a digital four track when I was 15.

When I started recording, a new world completely opened up and I really understood it as a medium that was something that I could fully create. For me, producing audio, even if it’s simple, has as much artistic expression as the notes themselves.

I also ended up studying architecture in undergrad and right after that I was working for visual artists as a studio assistant combining architectural and sculptural work. As an antidote, music became more of a creative outlet. I was spending eight hours a day creating visual art so there was just no way that I would come home and start making a sculpture. That’s when music started to become more and more of a creative focus. The more I explored and got into it, I understood how music also encapsulates all of these other mediums.

Music is spatial. It is temporal. It is social. It is performance. It is fixed media. Not to mention, there’s all the avenues for collaboration with visual artists, film makers or animators. There are so many ways that it is inextricably connected to other forms of media.

If you pursue music full-time, aren’t you worried that you’ll need another sort of creative outlet?

I think that already happens naturally. A lot of times if I’m mixing something and listening to the same thing over and over, I’m drawing as a way to listen to it without focusing too hard with my full attention. It’s a way to listen in an oblique way, and an example of how these interests naturally balance out.

In the beginning of quarantine, when I didn’t and couldn’t make music, I started writing, which I also really love. Texts have always found their way into my performances. The ways that I work on visual art or envision music will overlap or inform each other.

You’re very drawn to digital music. Do you also incorporate other instruments from jazz and classical music into your work?

Yeah, definitely. On ‘Recent Futures’, each track is focused on an acoustic instrument. The tracks include recordings of myself recording objects in a steel drum, improvising on a koto or even knocking on wood.

I don’t actually have a lot of musical equipment. I don’t collect synths or anything like that, but I have tons of weird small percussive instruments and I would like to have more acoustic instruments.

Ultimately, my process really begins once things start to get edited or arranged. Mostly, I start by generating as much as I can and then I carve away or distill it, until there’s some sort of crystallization.

Does it stem from experimentation mostly or where does the trigger come from?

I guess it depends on what it’s for. The music I make for myself is ‘non-programmatic,’ as in it’s not for anything, whereas music that is within a collaboration or for a score is ‘programmatic,’ it has a purpose or is expected to function in a certain way.

When I make music for myself, it’s often very intuitive. As I’m really interested in temporal perception, I try to grasp and express those different experiences, like time accelerating, or opening up into linearity. It’s an effort to make structures or spaces to create snapshots of time.

When I’m making music for a score or a collaboration, it’s approached with more of a clear intention and is usually very mood based. Like this should be ‘exciting’ or ‘very intense’ or ‘very sad,’ so often that does start from an overall vision of functionality.

When you make that kind of music, do you have to be in that mood to be able to generate that music?

Something I think about a lot is the idea of balance. Even if I don’t set out to make music through an emotional tone, I see that often my opposite is externalized to find balance.

A lot of the most pleasant or most beautiful music – if I can say so myself – that I’ve made was often made in times of hardship or anguish. On the flip side, when things in my life are very stable, positive, or maybe even boring, the music I make might be more overstimulating or high energy.

The way I make music has as much to do with listening as with playing an instrument. So often, I find that if I’m making music intuitively, I’ll be making music that moves towards what I need or want at the moment. Whether it’s my external environment or my internal emotional landscape, I find that music plays a role in trying to temper and balance – both in the way I make and consume music.

Music will always be emotional. It’s not a neutral medium. No matter what, the way you hear it and the way it affects you will always make it an emotional medium. There are so many subtle shades of emotion that it creates, so it’s impossible to escape.

Does architecture still seep in through your music practice?

When I studied architecture, my main interests were the temporal aspects of the space and the ways that people use a space over time affects the space itself. I think those aspects of temporality and social activation remain key interests of mine in the musical sphere.

You were also doing quite a lot of shows before the lockdown. Do you have a preference in terms of a concert set up?

Text-based videos have been an important aspect of my performances. I’ll write these texts that are a series of slides, usually based on dreams that I’ve had. A lot of times they’re pretty mundane, but because they’re dreams, there’s something a little bit off about them. The videos loop, so they don’t start or end. I’ll project that and then do a mixture between having some sort of structure planned out for the set with a lot of room for improvisation. I also like to include an electroacoustic element to bring in the visual aspect of sound making and live processing to life.

My hope is that as I play these shifting musical emotions, it casts a different light on the text. For example, the text might say something simple like “I walked into a room.” Maybe in the beginning of the set, that sounds very neutral and positive. But then at the end of the set, I might be playing something very intense so when it loops around again, it could feel completely different in light of different music.

Have you actually been doing digital concerts or livestreams?

I’ve done a few and it’s pretty surreal. A performance without the social aspect is really different, obviously. In concerts there’s this type of dynamic social spontaneity. There’s a spatial-temporal musical experience where everyone is in the same environment together. There’s more common ground and that creates room for other things to emerge. When everyone’s isolated, like when everyone’s listening through their own speakers in different places, a lot is limited.

To end, we really like your ongoing list of questions and it would be nice to ask your thoughts on one of them. So here it goes: “what does the Internet sound like?”

You know, I write these questions since I don’t have answers myself! But I love this. This is a real test of how much I’ve been thinking about them.

So, Timothy Morton once wrote about ‘hyperobjects.’ Ideas that are so big, they’re impossible to define. An example he uses is global warming. It’s just beyond an individual’s capacity – we’re not equipped to be able to really understand the scale of it both in space and time. The enormity of micro variables that have created such an immense movement is impossible to pin down.

The Internet is similar, or at least it makes sense to think of it in that way, because it’s just such a massive, teeming collective entity. To try to distill it as a sound or in a sound is a big question.