Unraveling conventions with Kate Carr

From intricate field recording to cinematic design, the sounds we hear around us come from a position of choice—choice in what we capture, how, when, and why. And this, naturally, shapes our experience with each other and our environments. This question of possibilities lies at the heart of Kate Carr’s sonic practices. An early interest in glitch music expanded into her own explorations in field recording and its corresponding technologies.

Over the years, Kate’s recording and live performance practices have evolved in parallel to the questions and reflections that have captivated her along her sound journey. With early works driven by experiences at residencies and capturing those environments, her current focus lies beyond field recordings themselves and more so on recording technologies, untangling and playing with recording techniques and how they shape sound and our means of connecting with a space and one another.

We enjoyed Kate’s thoughtful reflections on the authenticity of field recording, incorporating everyday sounds into practice, and examining our relationships with sound. She reminds us that there is so much possibility when we take the time to listen closely.

Could you take us back to the start: what sparked your interest in field recording?

I think it all started with listening to glitch music and trying to emulate those glitchy sounds from CD skips. Back then, I only had access to subpar equipment, so all I had were poor-quality, essentially failed recordings, which I suppose aligned with that glitch aesthetic of embracing malfunction. In the process, I discovered labels active in this genre, many of which were also releasing works based on recordings.

From there, my interest expanded to include sounds from both natural environments and human-built settings. I started educating myself and gaining access to information on how I might become a better field recorder, moving from just recording failures to actually having some kind of skill and knowledge in that regard.

What does it mean for you to become a better field recorder?

I think my practice has evolved a lot over the last 10 years. When I started out, it was all about grappling with a whole set of technologies that were completely new to me. The focus was on learning how to use these technologies, figuring out what I could afford, and setting up to record the kinds of sounds I wanted. In the very early stages, it was mostly about mastering those basic things. Now, it’s funny because almost all the field recorders I know, including myself, hardly ever do field recording anymore.

What I consider to be good practice in field recording has completely shifted. Now, it’s about the ability to create something that conceptually hangs together. A work should have various layers and different components that work together to communicate or evoke emotion, whether those are performative elements, technological aspects, or compositional features. I think that’s what I am mostly interested in exploring and doing – creating works that utilize these diverse elements in meaningful ways.

You’ve mentioned composition. Could you describe your process? Can you walk us through how you compose your work?

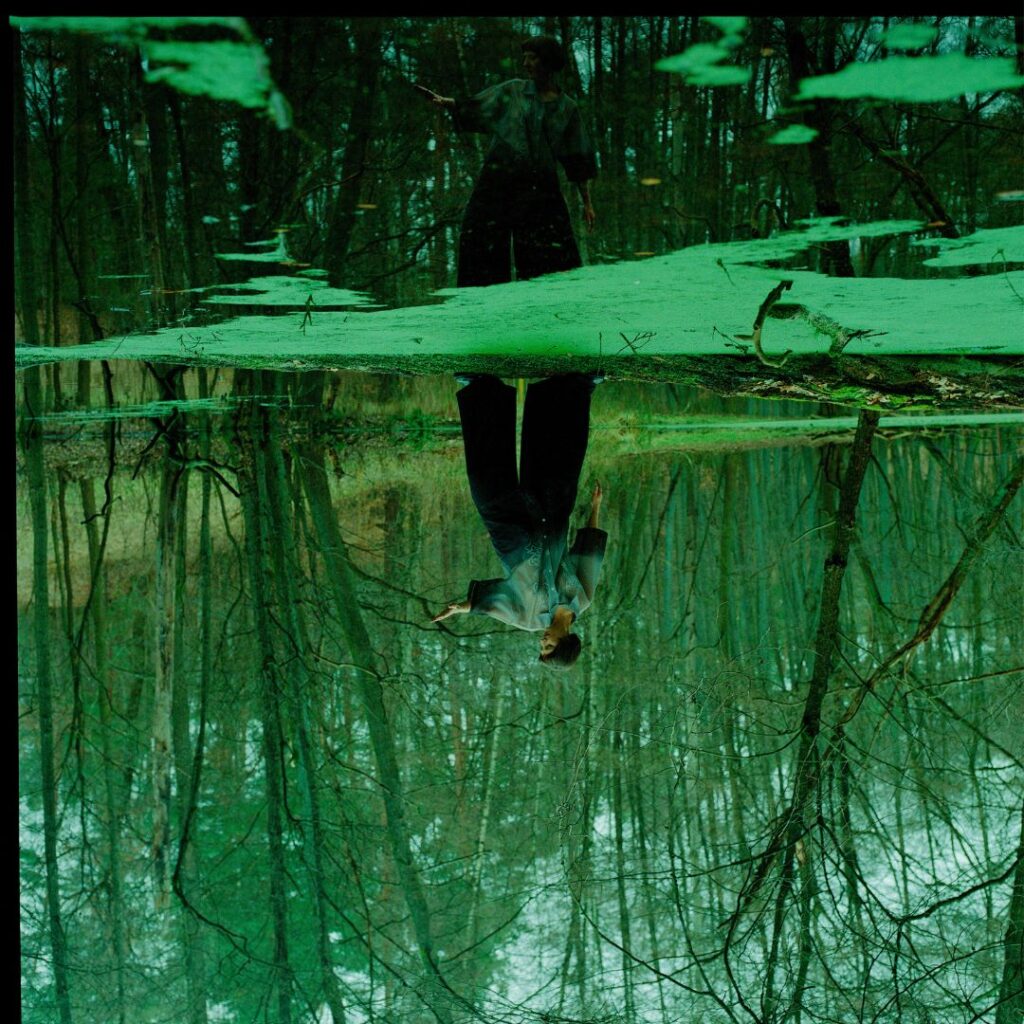

In my early work, my composition process was often shaped by residency situations. I’d go somewhere, initially feeling lost, questioning why I was there and what I hoped to gain from the experience. This often led to an intense period of work, where I would immerse myself completely for a considerable stretch of time. These residencies were extreme in the sense that they involved a lot of physical effort, like walking for hours on end while carrying heavy equipment. There was also that aspect of navigating the strangeness and unique dynamic of residencies, where people come together for various reasons, forming different kinds of relationships with the space and each other.

For about two years, this was primarily how I worked. However, things have changed significantly since then, especially since I’ve been mainly in London. My work has evolved to explore themes not tied to specific locations but more to emotional states or acts of connection. I also became interested in sound as a medium of communication, leading to a series of works centered around this theme.

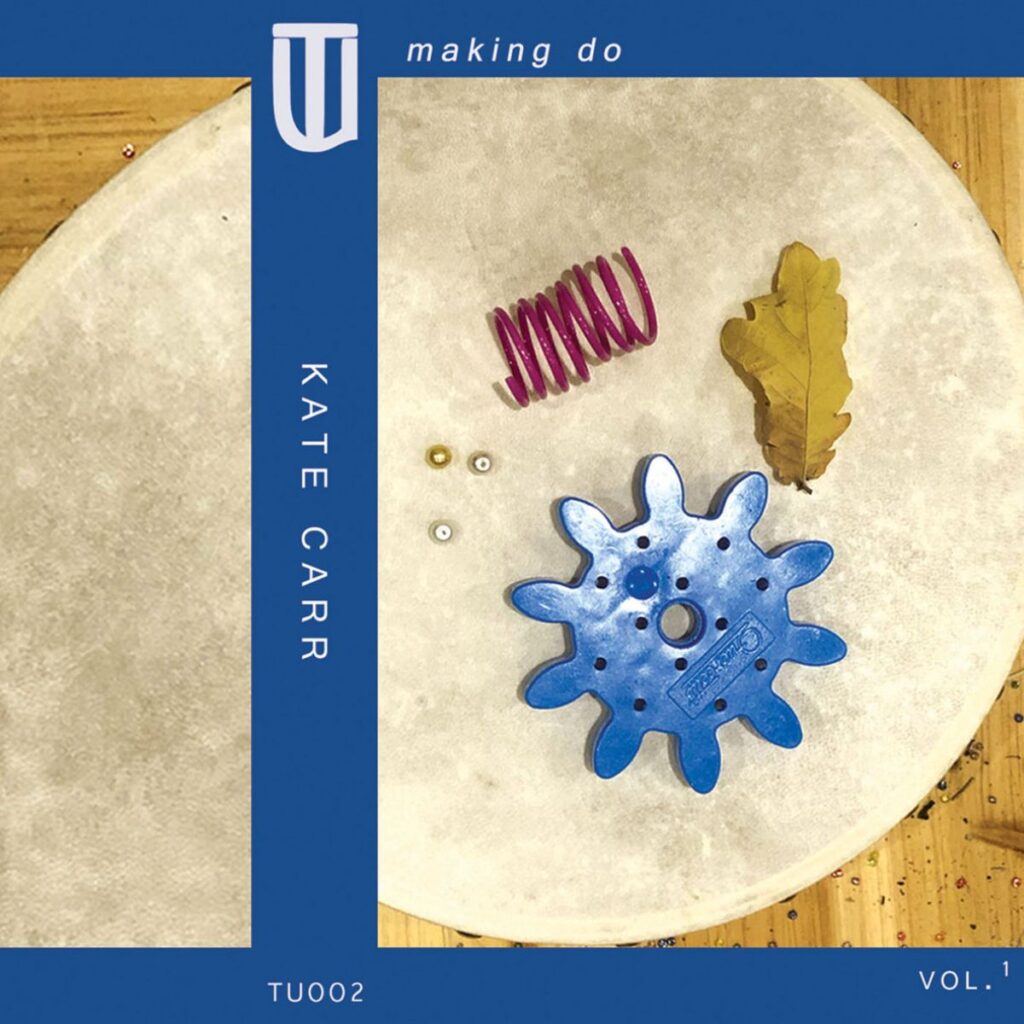

Currently, I work mostly from my flat, which isn’t ideal because of the noise. Random sounds like sirens sometimes creep into my recordings. Despite this, I enjoy carving out my own creative space, improvising with various found objects at home, and experimenting with different microphones and recording techniques. This approach feels more rewarding to me, as I prefer not to rely entirely on my computer. I like the physicality of standing up and moving around, working with my hands, and engaging more directly with my environment.

So, to revisit your question, my process has evolved from the emotionally and physically intense experiences of residencies to a more contained and introspective approach in my flat. It’s less about navigating the complexities of new environments and relationships and more about exploring internal emotional landscapes and themes of communication and connection within the confines of a familiar space.

Your practice has evolved significantly. What’s been one of your biggest learnings over time?

One of the most valuable lessons I’ve learned for my practice is the importance of taking a break: doing something else, taking the mind off things, and then returning to my work refreshed. I’ve found that incorporating breaks as part of my process has significantly strengthened many of my projects.

Recently, some of my students asked me about structuring their practice. There’s a common misconception, especially among artists, that inspiration requires constant work. We’re conditioned to think that relentless work is the key to being productive and, for artists, to feeling inspired and validated. But in my experience, working excessively is not how I come up with the most interesting ideas or produce my best work. Beyond avoiding burnout, it’s just so important as a human being to rest, nurture other interests, and maintain relationships outside of one’s practice.

This is especially true in sound work. When engaged in tactile activities, you can instinctively feel when your body needs a break. Just like your hands might need rest after physical labor, your ears can get tired from constant auditory input.

You once shared with us your enjoyment of combining field recording and live foley work, especially in performance. What is the intent behind merging these approache? What do you like about it?

It aligns with my desire to move away from solely relying on the computer. Particularly in performances, my goal is to make transparent the process behind the sounds the audience hears. I’m interested in exploring both the technologies that produced these recordings and the use of objects, whether related or unrelated, that can evoke textures and moods captured by field recordings.

I recently attended a talk by a professional foley artist and I found it interesting to learn about the various materials and approaches used in that industry. It’s very different from a field recording-based practice. I find it intriguing to be a field recorder moving towards foley, attempting to create sounds that are based on field recordings using objects.

In contrast to foley, which has shaped our sound expectations through cinema, field recording is more about exploring actual sounds captured in the environment.

You touched on the idea of transparency. Why is that important for you?

What I like about live foley work is that it challenges the notion of authenticity. It allows you to create sounds that closely resemble familiar sounds that you know.

And how important is authenticity to you when it comes to field recordings? What does authenticity mean for you?

It’s a timely question in field recording and in thinking about field recording today. Some might argue, and I tend to agree, that every recording is essentially an authored and performed document. It encompasses not only the recorder’s decisions regarding microphone placement and other obvious factors, but also decisions about what sounds to include or exclude and how to edit the recording. In essence, every recording reflects the choices and shaping decisions made by the recorder. This raises a question: can it really be considered an authentic representation?

Performing live, whether by recreating or attempting to create a fiction, offers an intriguing way to reflect on the nuanced decisions inherent in field recording. That’s how I’d like to think of it anyway. In many ways, my practice is deliberately moving away from claiming any sense of authenticity. I’m more interested in exploring recording technologies and performing reenactments of recordings, experimenting with the possibilities they offer.

Do you also incorporate elements that aren’t even there in the first place?

My EP “False Dawn” is all about stuff that’s not really there. Inspired by dawn choruses recorded during various field recording workshops, I decided to create a studio version. It’s a completely inauthentic creation, obviously and deliberately so, diverging far from the traditional notion of not altering recordings. In my work, I almost always add something conspicuously absent, like instrumentation or a drone.

I feel like I’m slowly leaving the field recording aspect completely behind in my practice. It’s becoming more like an absent center – it used to be the foundation, but now, even though it remains a reference point, it’s not always directly present in my pieces. My current interest lies in adopting the techniques and technology of field recording to build my practice. Initially, this began with a focus on space – using and gathering sounds from specific locations to narrate our relationships with those spaces and our movement through them. I’m still interested in all of that and I remain interested in field recording, but now it’s more about playing with its conventions and thinking about how to use the technologies and performance skills I’ve learned in ways that are becoming less directly related to field recording. It’s still very much about how the contour of sound shapes our experiences of the world, just expressed differently.

Is there a specific sound that has profoundly influenced your work?

I always incorporate a drone in my work. It’s central to my practice, although I can’t fully elaborate why. Without a drone, my work just doesn’t sound right to me. Drones embed a constant presence in my work, setting the emotional tone and acting as a backdrop for the other sounds I work with. It’s not something I consciously think about, but they’re always there.

Recently, I’ve been experimenting with a bicycle, mounted upside down over my computer, and contact mics to produce different sounds. Using short drones from my keyboard, I notice that when I omit them, I almost always feel compelled to reintroduce them. People might not perceive me as a prominent drone user because drones don’t take center stage in my work. However, they’re almost always there, subtly underpinning everything.

As we’re talking about bicycles, another constant in your work is the use of everyday objects. How do you draw inspiration from mundane sounds, and how do you decide to incorporate them into your compositions?

Field recording is evolving and expanding, especially considering its history in documenting anthropology and capturing natural, pristine soundscapes. The new generation of field recorders is increasingly focusing on private and domestic spaces, using their home environments as the basis for their field recording practices, which I find fascinating.

In my own work, coming from a background that isn’t particularly focused on anthropology or documentary filmmaking, I often think, “Why not use these sounds that I hear all the time?” My work often revolves around space, emotionality, connection, and relationships, so naturally, the sounds of everyday life objects are at the heart of it. For me, it’s very natural to turn to these objects and explore the sounding possibilities of the objects I encounter regularly.

Building on the idea of using everyday sounds in your work, how did you develop an interest in finding inspiration in public spaces or spaces in general?

I think it stems from living in the world and just thinking about how we exist as social creatures, how we relate to each other, and our collective experiences.

As my practice began with residencies where people from diverse walks of life are thrown together and maybe are working through a lot of different issues, this made me contemplate how my experiences of those locations would have differed with a different group of people or if I were alone. It kind of set me on a path to use sound as a tool for exploring how different relationships shape our experiences of a place at a specific moment.

I think of sound as a powerful medium for exploring such dynamics. It allows for equal parts expression and silence, giving us numerous tools for understanding our relationships with each other. I also think that soundscapes provide insightful depictions of our interactions, demonstrating how we express ourselves and choose silence in relation to one another.

I have always found sound a profound method to understand our place in the world, our connections with others, and how we might also choose to stay quiet to let other people be heard.

You seem to reflect deeply about your practice. How do you envision it evolving going forward?

What do I envision for my practice? Wow, you’ve caught me at an interesting moment, as I’m just beginning to plan what my next year or two will look like. Until now, my approach has been quite reactive, and I’ve been very lucky that things have come to me. Moving to London, being in a PhD program, and responding to the pandemic have left me with little time to deliberate on what I want my practice to be like. This is a common economic reality for many who live, to some extent, through their practice.

At present, the most important thing for me is to take some time to really think about that question. I’m keen to continue my work with objects and am eager to delve more into installation-based work. For now, my priority is to take stock and deeply reflect on my practice, allowing my current interests to guide me.

Another goal is to establish a more regular practice, not necessarily daily, as that seems overly ambitious and unrealistic, but perhaps a few times a week in the studio. This would allow me the freedom to explore sounds without the pressure of needing a specific outcome. Much of my work has been outcome-oriented, so I would just like to sit in my studio and see where the sounds lead me.