Through the years with 12k

Founded in 1997 by Taylor Deupree, the label has built a catalog grounded in patience. Sound is treated as material rather than message, with attention to small shifts, slow movement, and silence. Music that doesn’t ask for immediacy, but for time.

Over the years, 12k has remained consistent without becoming fixed. Its releases focus on space and texture, on how sounds sit alongside one another, and on what becomes audible when very little changes.

“Selecting a handful of releases from the 12k catalog is not an easy task,” Taylor shares. “There are many personal stories, connections, and friendships behind each release, and these came to mind because each contributes an important aspect of what 12k is about.”

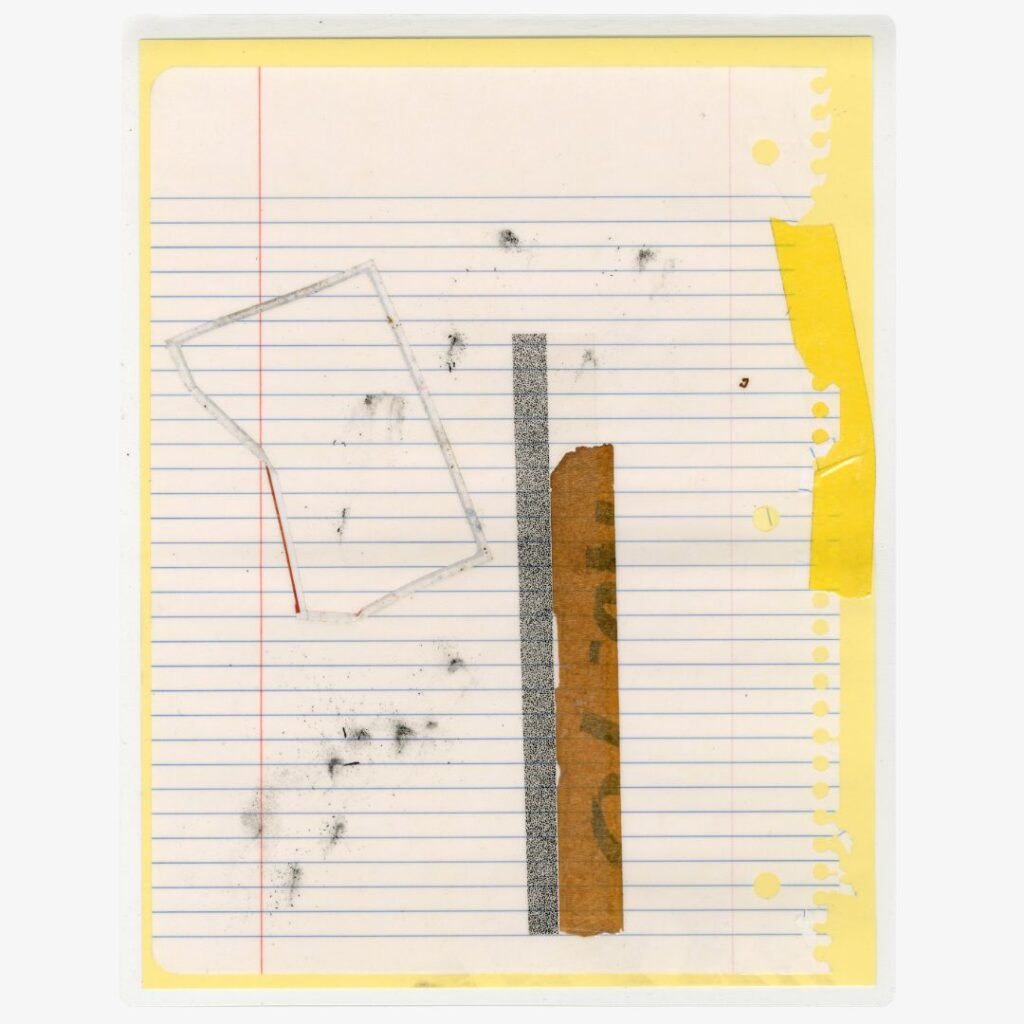

Marcus Fischer – Monocoastal (10th Anniversary Edition)

Marcus needs little introduction for 12k listeners. His debut for the label, Monocoastal, receives a beautiful vinyl edition with artwork by Gregory Euclide. Marcus is here because 12k is all about family and community. I consider him one of my dearest friends, and the label would not be the same without his presence.

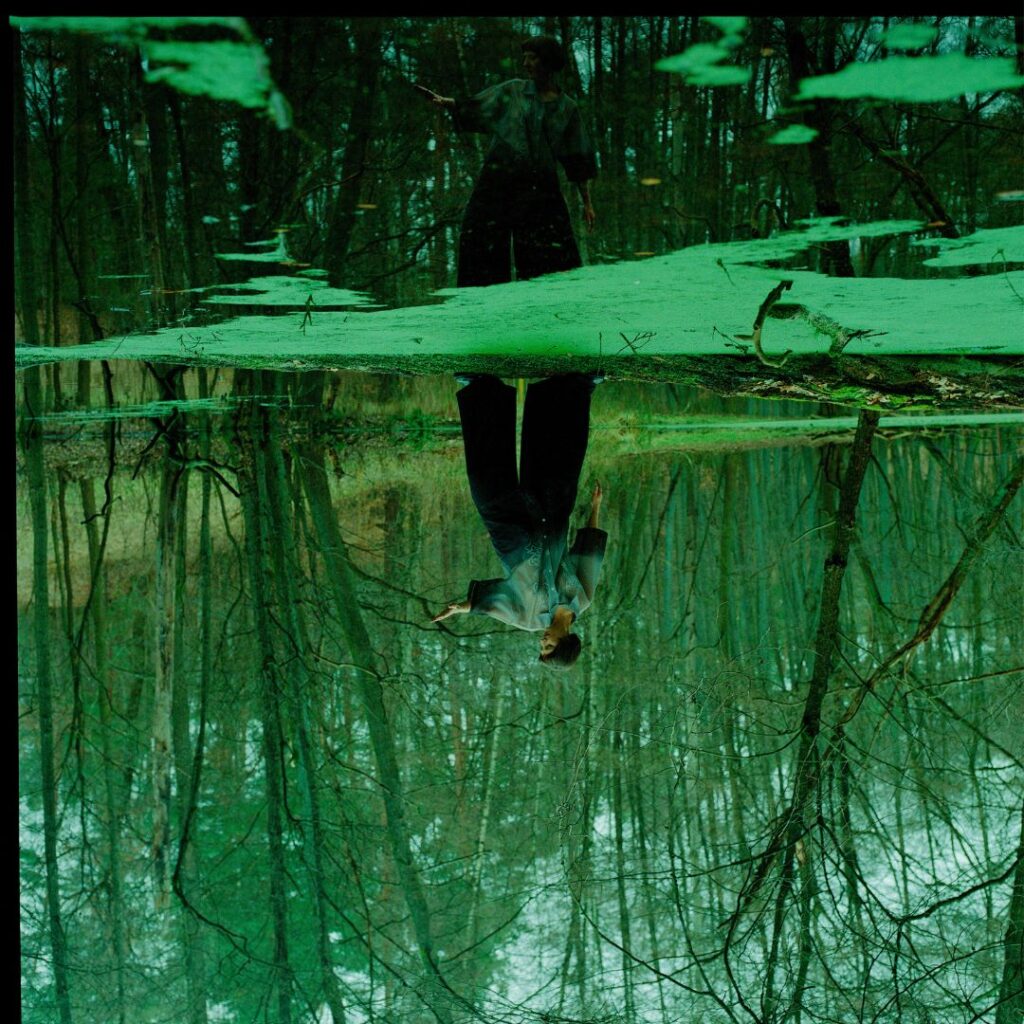

Pjusk – Salt og Vind

Nature and environment, one of 12k’s most essential aesthetics, are reflected here through Pjusk, who channel the landscape of Norway in all of their music. While I’ve never been, Pjusk’s music feels like the perfect soundtrack to its landscape. Simultaneously icy and warm. Sprawling, open, glacial.

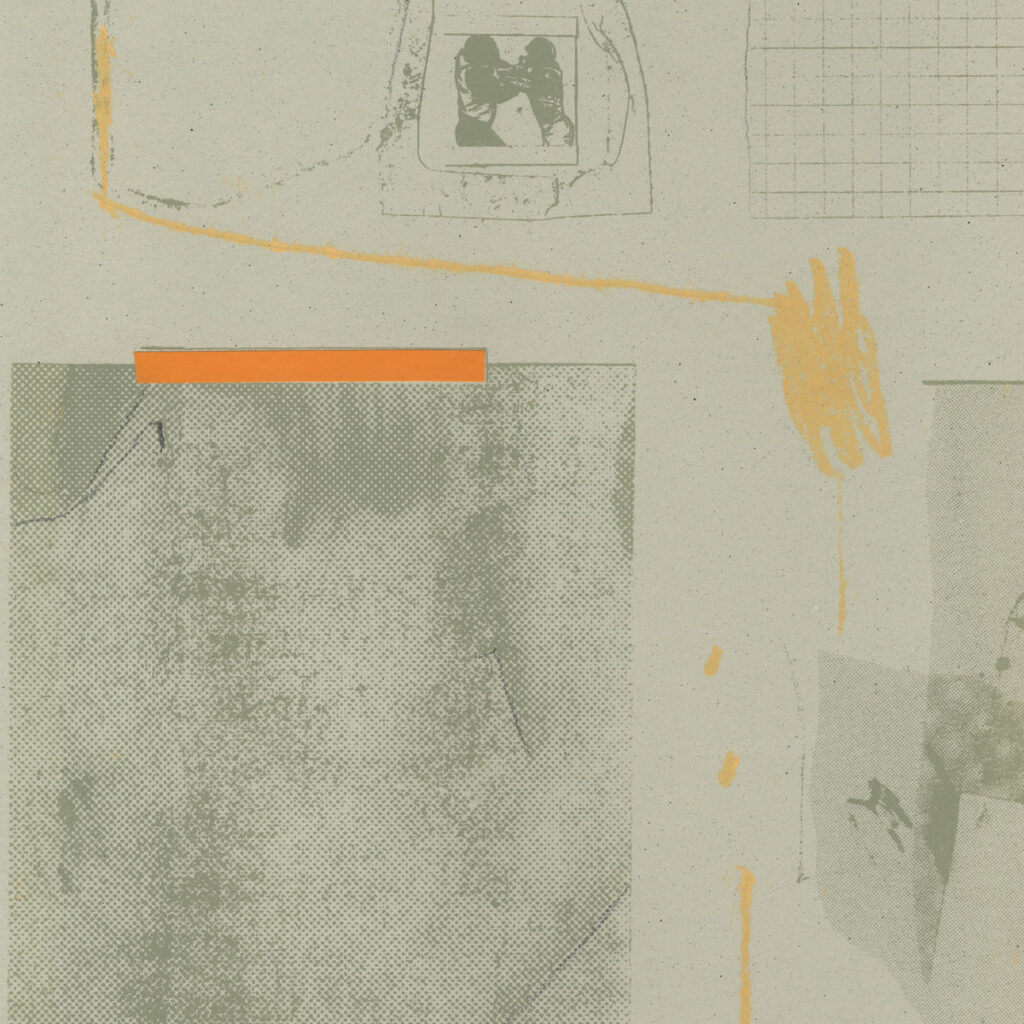

Giuseppe Ielasi – Five Wooden Frames

Giuseppe is perhaps the most underrated solo guitar manipulator in our extended musical space. His music, marked by reduction and simplicity, makes you stop what you’re doing and listen, whether he’s playing the guitar more traditionally or unearthing new sounds and textures. 12k has been releasing his music for many years, and hopefully for many more to come.

Gareth Dickson – Orwell Court

Gareth is a bit of an outlier on 12k, the only fairly straightforward singer-songwriter centered on vocals and lyrics, something quite different for the label. Yet when you listen to his music, it makes perfect sense. One of 12k’s core principles is “Evolve constantly, but slowly,” and I don’t think any artist represents this evolution better than Gareth Dickson. There’s a fragility and a sense of space that are key components of the 12k sound, and Gareth’s entire catalog blows me away. It’s a total honor to have him as part of the label.

Steve Peters & Steve Roden – Not A Leaf Remains As It Was

Steve Roden left us far too soon, yet he left behind a huge catalog of music and art. Collaborating here with his friend, “the other Steve,” we get what is perhaps my very favorite music amongst Roden’s numerous releases. He was known to occasionally use his voice in his work, and it always sounded reserved, gentle, and perhaps a little broken or shy. When it shows up on this album, it immediately makes it sound like the Steves are in a small room, creating only for the listener.

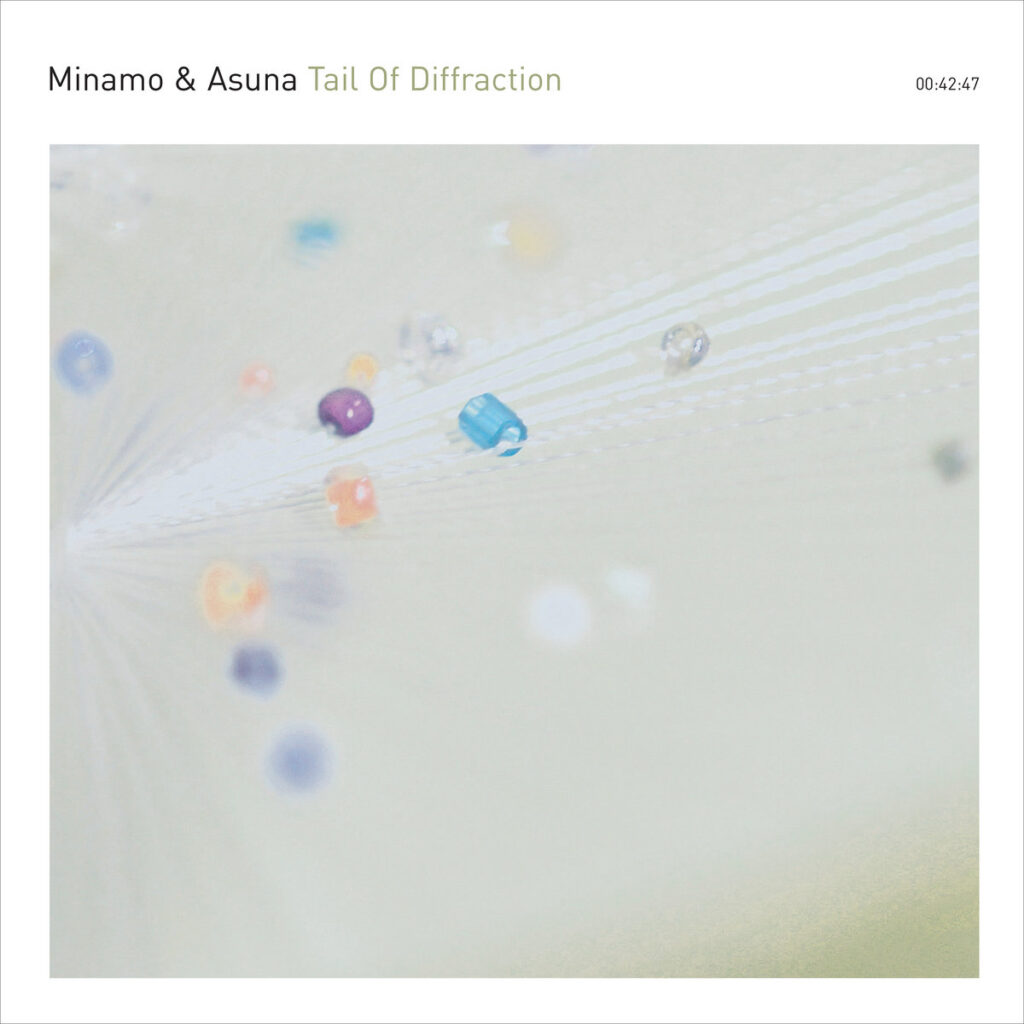

Minamo & Asuna – Tail of Diffraction

Minamo has been part of 12k for a long time, helping to define the label in its early years. Teaming up here with Asuna, who is well known for his amazing “100 Keyboards” piece, was a way to bring two of my favorite artists together in a single release. Heavily rooted in acoustic instruments yet textural, like no one else can do.